Co-published by our media partner, The Dallas Weekly

Parts of South Dallas and Fair Park are using self-imposed tax dollars to improve the community by cleaning up streets, fixing infrastructure issues and increasing public safety and security.

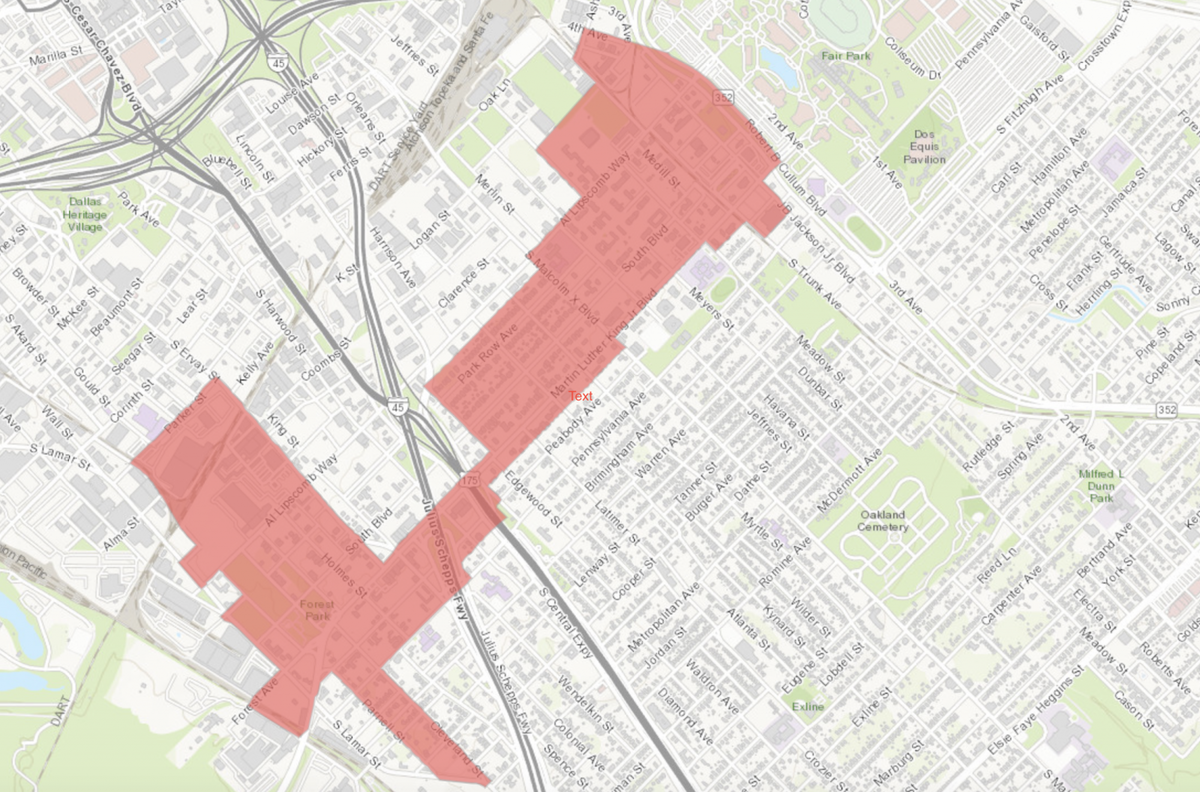

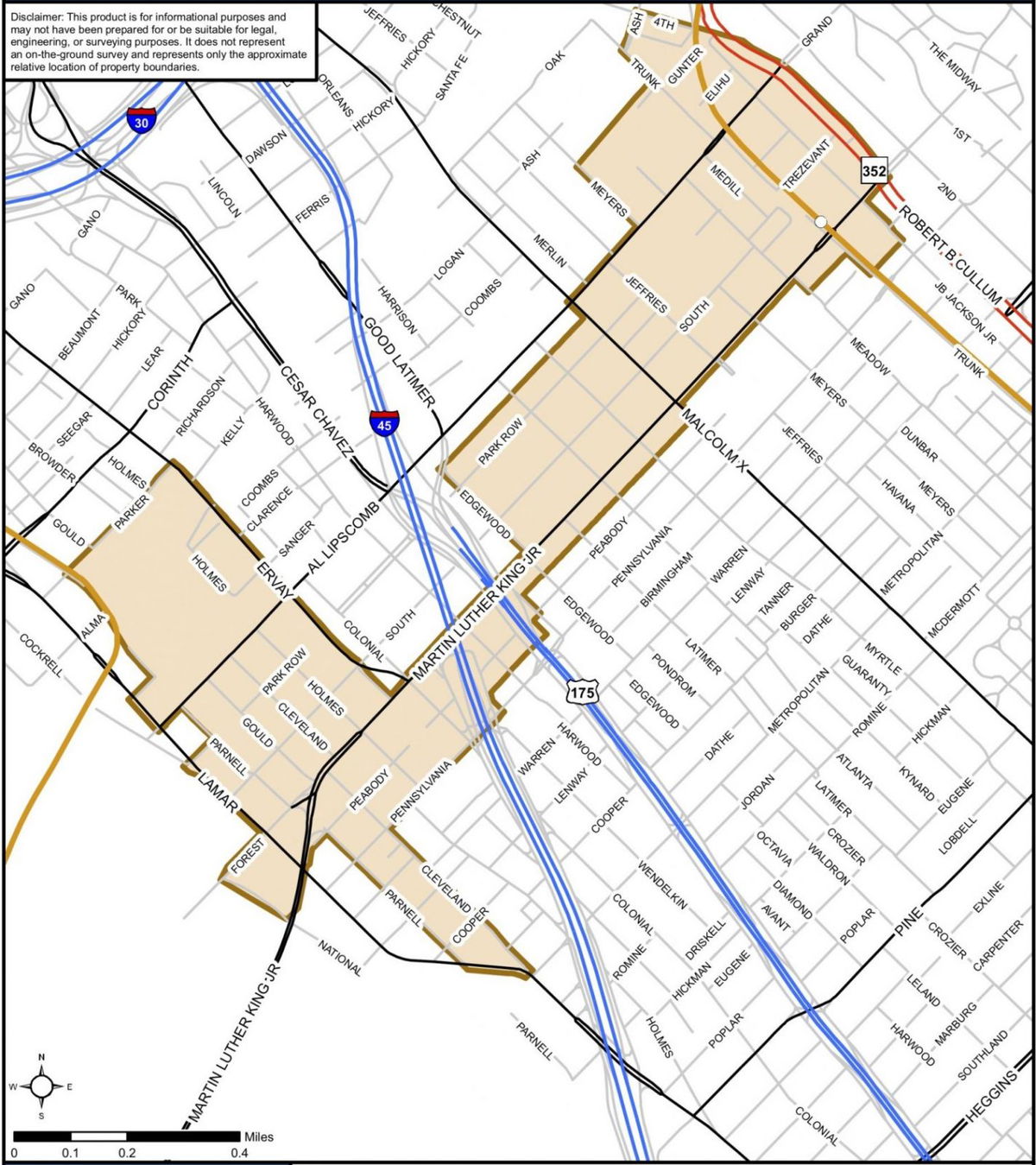

The area is doing this through the South Dallas Fair Park Public Improvement District, or PID, managed by the nonprofit organization South Side Quarter Development Corporation.

Roughly 630 properties are part of the South Dallas Fair Park PID, both residential and commercial. These property owners pay an extra 15 cents per $100 of their property value to the City of Dallas each year, and that money is funneled to South Side Quarter, which determines how the money is spent.

For example, if someone living in Fair Park Estates owns a home that the Dallas Central Appraisal District values at $150,000, that homeowner would pay $225 annually to the PID.

This 15-cent assessment is in addition to tax dollars residents and business owners already pay each year to the city, Dallas ISD, Dallas County, Dallas College and Parkland Hospital. Dallas has 14 public improvement districts across the city, and according to its website, a PID “allows for groups of property owners to request special property tax assessments for the provision of services above typical City of Dallas levels,” which may include “marketing the area, providing additional security, landscaping and lighting, street cleaning, and cultural or recreational improvements.”

South Side Quarter is an offshoot of Matthews Southwest, the real estate company that oversaw projects in The Cedars, such as the Alamo Drafthouse. South Side Quarter also oversees the PID for that area, the South Side PID. Shannon Brown runs South Side Quarter and says she is paid by Matthews Southwest, not via the PID taxes.

Since its establishment in 2016, the South Dallas Fair Park PID has been through its share of controversies. In 2018, the PID had a different management company called Hip Hop Government, which took the money and disappeared.

Brown says her development corporation has no affiliation with Hip Hop Government and never received any of neighbors’ tax dollars before they took over in December 2018. South Side Quarter released its 2019-20 overview in late July, and the numbers show that the nonprofit is investing citizens’ money back into the community.

When South Side Quarter launched, Brown says they met with key stakeholders and other members of the community to determine the most pressing issues. Feedback from meetings, which took place from March to May 2019, indicated that priority areas were lighting, public safety, panhandling, more community events and clean-ups.

Over the past year, South Side Quarter hired Miles of Freedom, a local nonprofit that offers jobs and resources to individuals being released from prison. Miles of Freedom was hired to be the lawn care service along main roads within the PID boundaries and to clear out alleyways in the South Blvd/Park Row neighborhood.

The PID also launched the MLK Clean Team, which consisted of volunteers picking up trash and helping with the mural painting at the MLK Community Center.

Other investments were made to local parks, community events, an audit and recruitment, including $1,200 to the Dallas Weekly in November 2019 to promote the PID.

Courtesy patrols also have been activated within the PID to report 311 violations, mainly consisted of litter issues.

The PID took in $106,087 from South Dallas Fair Park neighbors’ and business owners’ 2019 assessments, and spent $70,013 on community improvements. It expects to receive more than $120,000 in 2020 assessments, a number projected to nearly double by 2024, as property values rise in South Dallas.

When asked about the potential for gentrification in and around the PID boundaries, especially since South Side Quarter is an offshoot of Matthews Southwest, which redeveloped The Cedars area, Brown says the PID is not something that was brought to her by management. She said she was asked by someone outside of the company to work on it.

“It was something that I wanted to do that I brought to my bosses,” Brown says. “This wasn’t even on their radars. This was my passion.”

Moving forward, the Dallas Innovation Alliance — a group of stakeholders, corporations and other individuals in the city who work to help Dallas become a “smart city” — laid out plans on how to improve lighting, public safety and other issues that have been brought up by community members.

Leave a Reply