When school started in August, 329 seventh- and eighth-graders reported to L.G. Pinkston High School. The campus has housed both high school and middle school students since fall 2018, when Dallas ISD closed Thomas Edison Middle School.

But this year, though the seventh- and eighth-graders are at Pinkston’s campus, they’re in a separate school with a unique learning approach — the new West Dallas STEM school, born from a partnership between Dallas ISD, Southern Methodist University’s Simmons School, and the Toyota USA Foundation.

The partnership’s goal is to give West Dallas students access to quality education around STEM — science, technology, engineering and math — and also to support students and their families by integrating “wraparound services” on the campus. Wraparound services provide holistic support for students and their families, taking into account lifestyle needs, such as enough food to eat and access to transportation. The partners’ hope is that this comprehensive support will make it easier for students to focus on learning, and increase their opportunities to excel.

The STEM school has its own curriculum, developed by the Simmons School, and its teachers use a unique inquiry-based model. This means teachers are still responsible for ensuring students learn certain TEKS, knowledge standards set by the state of Texas, but they give the students liberties to decide how they’re going to absorb the knowledge.

“The teacher kind of sets the stage,” Principal Marion Jackson explains.

Instead of receiving a typical lecture, students are encouraged to give input and ask questions about subjects that pique their interests. They learn through tinkering, making observations and doing projects related to their overall learning goal. Jackson believes this allows students to take ownership of their studies.

“By doing [this],” she says, “you’ve opened up a whole new world to kiddos, where they really feel involved, they feel engaged in what they’re learning.”

The goal is also to build resilience in students and to encourage them to work through difficult problems, says STEM school project manager Karen Pierce at the SMU Simmons School of Education.

“We talk about persistence and being successful in a career — being able to go to post-secondary, whether it’s college or whether it’s career training,” Pierce says. “If something gets hard or something is difficult, we want them to be able to push through it.”

Pierce says she believes West Dallas students are perfect for the inquiry-based model because the community is “perseverant” with a “deep, rich culture and a unique perspective.” Neighborhood students bring a variety of background knowledge and skills into the classroom, she says, and “the more varied that is, the stronger your inquiry instruction.”

At first, Jackson says, the seventh- and eighth-graders were hesitant to adopt the inquiry-based model, but as they begin to understand that their teachers genuinely want their input, they’re getting accustomed to and embracing the hands-on approach.

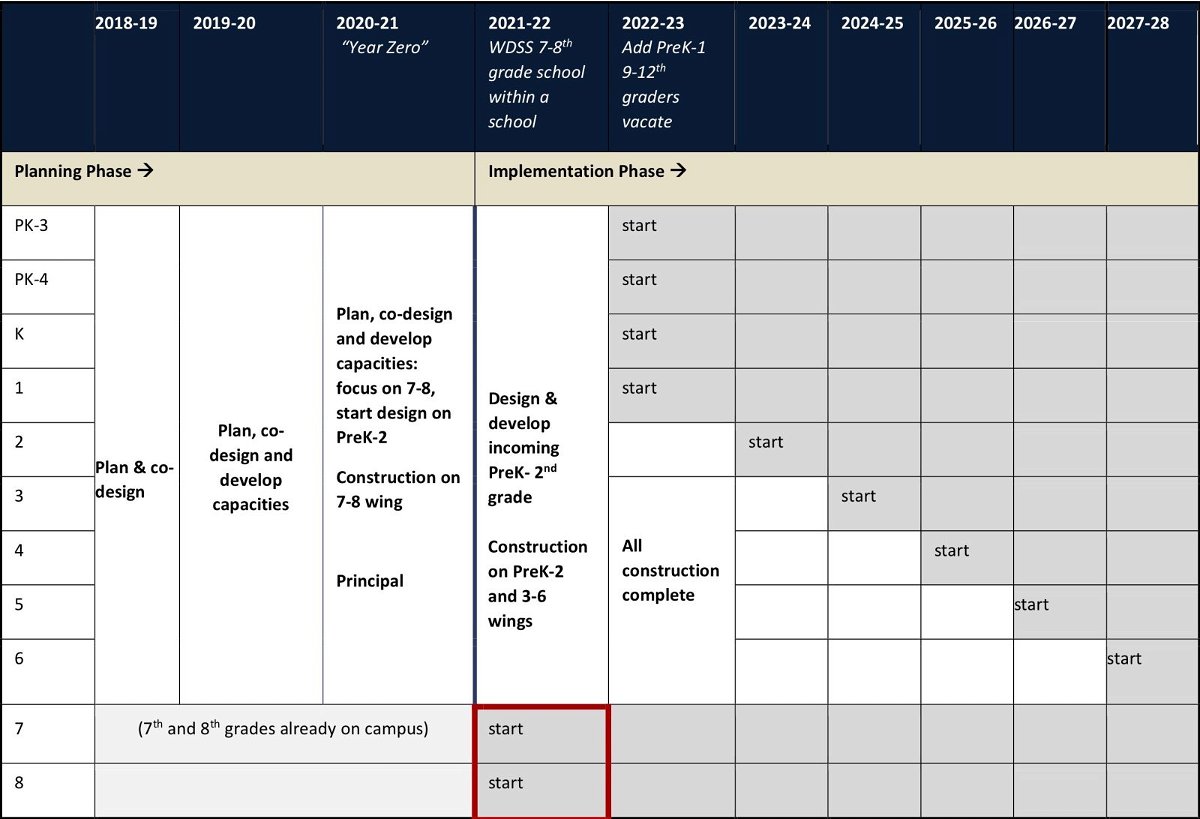

By fall 2022, the school should have a building that reflects its curriculum. The West Dallas STEM School program is part of DISD’s $2 billion 2015 bond project, which dedicated $35 million to renovate the school. Notable projects include new STEM labs, STEM-based courtyards and updates to administrative offices and classrooms.

Once ninth- and tenth-grade students move to the new Pinkston building on the corner of Greenleaf Street and Holystone Street, the campus will be dedicated to pre-K through eighth-grade students. Pinkston High School students are scheduled to move into their new building in January 2022.

Ample funding is another thing that sets the school apart — not just the $35 million in bond money but also $5 million from Toyota USA Foundation’s grant program, which supports STEM-based education efforts. Toyota provided $2 million in 2018 to support the school’s planning phase, and another $3 million in May 2020 to support the school through June 30, 2024, the end of its third full year.

Those millions are on top of the school’s dedicated DISD budget, which funds everyday operations like classroom materials and on-campus resources. All of this makes the West Dallas STEM school a well-funded endeavor, says Jackson. The extra funding allowed Dallas ISD to hire her a year early and spend a full year preparing for the school’s launch. This practice is not typical for the district, but was necessary for the STEM school’s partnership.

“The decision to onboard the principal a year prior to the opening of the school was integral to the school’s design and planning process,” said DISD in an emailed statement. “The principal played an important role in managing the four way partnership with SMU, Toyota Foundation, the West Dallas Community and Dallas ISD.”

Toyota’s more recent donation will support salaries of SMU faculty who are developing curriculum for the school and for hiring outside consultants when needed, Pierce says, explaining that because the STEM school project is so important to SMU, “we want to have the right voices and the right people and the right expertise, even if we have to go find it somewhere else.”

The $3 million grant also will compensate nonprofits providing wraparound services to the STEM school for their time and resources. Several West Dallas-based nonprofits are part of that group, including Voice of Hope Ministries, helmed by Ed Franklin. He also serves as co-chair of the STEM school’s advisory council, working closely with Jackson by keeping an ear to the ground and communicating with neighbors about what’s happening with the school.

DISD, SMU and Toyota are eager to mention there are actually four STEM school partners — the fourth is the West Dallas community, which should have equal voice and investment in the project, they say.

Franklin says most of the West Dallas community is optimistic about the STEM school. He understands the skepticism that remains, but believes Jackson’s intent to make the school a community resource.

“She’s doing all she can to make sure she follows through on that promise, and that the community trusts her leadership,” he says. “Because unfortunately, not just West Dallas, but many underserved communities have heard stories and promises … and [they] become a little bit jaded. Understandably so.”

The STEM school is a neighborhood school, but is expected to operate as a Dallas ISD “choice school” starting in fall 2022. This means students from other neighborhoods will be allowed to enroll. Fifty percent of students in the school will be from West Dallas, while the other 50 percent will be randomly selected via a lottery.

The school will welcome pre-K through first grades in fall 2022, along with the seventh- and eighth-graders. The school population will grow as the first graders move up, with new pre-K students added via lottery each year.

Jackson says though the partnership and her team is strong, their goal is constant improvement.

“What I can tell you is that we are perfectly imperfect,” she says. “Sometimes the most perfect plan does not give you the results that you thought once you put it into action. And so based on the feedback that we get from staff, from parents — even from students — we are always going back to the drawing board to constantly improve how we impact not only our students and staff members, but our community as well.”

Awesome article! I’m glad to see a well-funded, well-structured school in West Dallas