Raul and Juanita Reyes immigrated to Dallas in 1969. They became West Dallas homeowners a decade later, in 1979, and raised six children in the neighborhood. The Reyes family now owns several West Dallas properties, including houses that they, their children and grandchildren call home.

In other words, says their son, Raul Reyes Jr., the Reyes family has been investing in West Dallas for decades, just like many other multi-generational neighborhood families.

In 2018 Reyes Jr. convened several neighborhood leaders together to discuss the idea of a West Dallas equity plan. “We were all operating in our silos, all talking West Dallas but not talking together,” he recalls. The idea was to create economic mobility through land. “At the end of the day that’s what we have — our land — and how do we use that land to create opportunity for everyone who lives here?” Reyes Jr. asks. “How do we preserve our West Dallas?”

Not coincidentally, 2018 also was the year that hundreds of West Dallas properties spiked in value, especially on the east side closest to Downtown and to the more recent Trinity Groves development. On the one hand, long-ago investments were yielding dividends. On the other, many decades-long homeowners faced a property tax increase so sudden and significant that they feared being priced out of their neighborhood.

Now, three years after that initial conversation birthed the idea, a neighborhood-led West Dallas community vision plan will be developed over the next several months through a steering committee of West Dallas residents.

James Armstrong III, who was present at that 2018 meeting, calls the plan a “saving grace.” The West Dallas native and president/CEO of Builders of Hope says it will be “a seamless transition from plan to [city] policy.”

“All of this will be used to shape the future of West Dallas for the next 10 to 20 years,” Armstrong says, noting that the key question is: “How can we slow down the fast-paced gentrification that is running a risk of literally changing the thread of our community and wiping away the history?”

He recalls places like the Dog House on Singleton, where his parents and grandparents brought frozen treats — “those West Dallas landmarks that make West Dallas, West Dallas. Those images are being wiped away with big box development.

“This is an opportunity for residents to put to paper what they want their community to look like.”

Builders of Hope is leading the partnership between several groups including West Dallas 1, a grassroots coalition of neighborhood associations, of which Reyes Jr. is president. Trinity Park Conservancy is the convener, bringing the partners together to get the work done, says Jeamy Molina, the conservancy’s director of communications and engagement. The $150 million Harold Simmons Park is expected to stimulate $3.5 billion in real estate development, but the economic value it promises also threatens to displace residents of West Dallas.

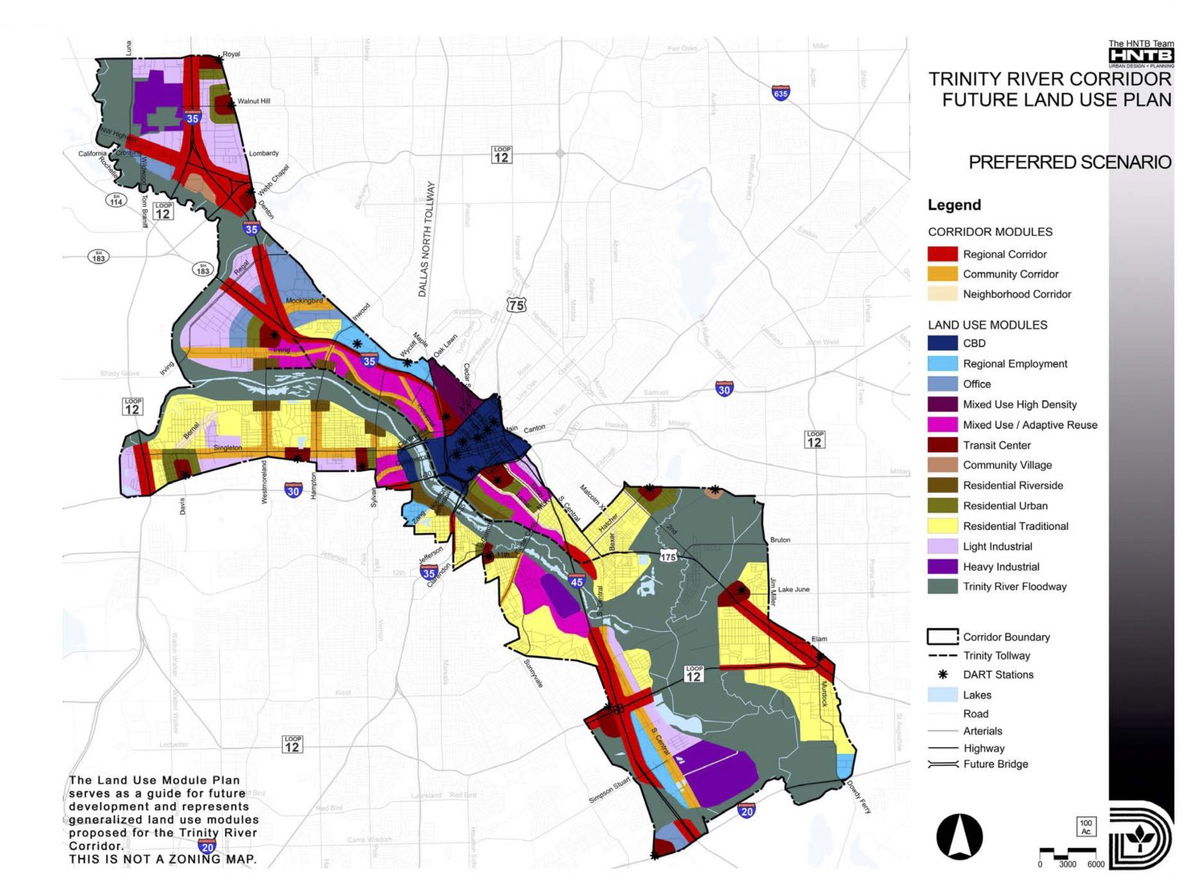

Neighbors in West Dallas and other communities along the river have “gone through over 100 plans of what should happen, what needs to happen, but nothing’s been done,” Molina says. “We want to make sure we have some teeth behind it and when this plan comes into fruition, someone’s going to be held accountable for it.”

The first step is identifying a 10- to 15-member steering committee of West Dallas residents who can engage their neighbors, put together a plan, and lead advocacy efforts to turn the plan into policy. Each member will be paid a $2,000 honorarium for their work over the course of six months, and anyone interested is encouraged to apply.

Reyes Jr. says it’s the perfect opportunity for young homeowners, or renters working to become homeowners, to get involved and shape the future of their neighborhood.

“A lot of residents would like to be engaged and don’t know how,” Armstrong says. “They’ve been quiet for a long time, not because they didn’t have a voice but because they didn’t know how to amplify it.”

“It can’t be [the conservancy’s] voice,” Molina adds. “The community has to come together and tell the city, ‘This is what’s important to us, and this is what’s going to fix it.’ ”

Communities Foundation of Texas’ W.W. Caruth Fund is backing the $300,000 effort, which includes a fair housing assessment of the 2.5 miles around Harold Simmons Park and all of West Dallas. Downwinders at Risk, which has been heavily involved in environmental justice efforts around Shingle Mountain, also will partner on the West Dallas plan, as will Southern Methodist University’s Budd Center on community collaboration and design thinking.

This plan will be different from the 2005 Trinity River Corridor Comprehensive Land Use Plan and the 2011 West Dallas Urban Structure and Guidelines because “the community’s voice will be at the forefront, and the goal of this plan is adoption,” Armstrong says. “West Dallas has not had a community-driven plan that has been adopted at City Hall.” He knows his neighbors are “really weary of the planning process, and at this point they want to see action,” and he emphasizes that “ this is the process necessary to go before the City Plan Commission or the City Council and say, ‘This is what the community wants — no more guessing, no more suggesting.’ ”

A plan like this should be the standard in the City of Dallas, especially in neighborhoods that are susceptible to gentrification, Armstrong says. Equitable planning should precede equitable development, he says.

In the real estate development, equity means that “instead of inviting the neighbors to the table, we should realize and understand, it’s their table,” Armstrong says. “These are people who have invested in this area when public investment did not exist.” Even when streets were unpaved, and running water and electricity weren’t available to homes, “these residents decided West Dallas was the best place to live for them and their families,” he says, “and they suffered a lot of social and environmental injustices because it was the only place they could afford, or because they were pushed there by pocketed poverty.”

“Equity in this case,” Armstrong says, “is making sure that those who have invested time and money in the community, that their voice is heard. They were there first.”

Open-architected

Fresh