Lea la versión en español de esta historia

Connie Ramirez remembers sitting on her godparents’ porch swing on Gulden Lane as a child, gazing from the La Bajada neighborhood across the Trinity River at the downtown Dallas skyline.

Jose and Eliosa Espinoza had no children, so Ramirez, who lived nearby in El Aceite, spent a lot of time at their modest 650-square-foot home, built in 1945.

“It has lot of good memories,” Ramirez says of the house. “They were well known in the neighborhood. They had little plaques for being ‘outstanding community members.’ ”

Jose Espinoza died in 2013 and left the house to his goddaughter. When Ramirez’ daughter moved in, there were still homes across the street on lots that backed up to the Trinity River levees. They saw “no sign of development,” she says.

Within five years, Ramirez says, “our taxes jumped from $600 a year to $3,000. It felt like that was their way of trying to push us out of the neighborhood.”

The house now sits across the street from 3.76 acres of scraped and undeveloped land, currently acting as a parking lot for Trinity Groves restaurants and retailers. The developer of Trinity Groves, West Dallas Investments, has been buying parcels in the neighborhood for more than a decade with 127 properties now in its portfolio, according to a Dallas Free Press analysis of Dallas Central Appraisal District records.

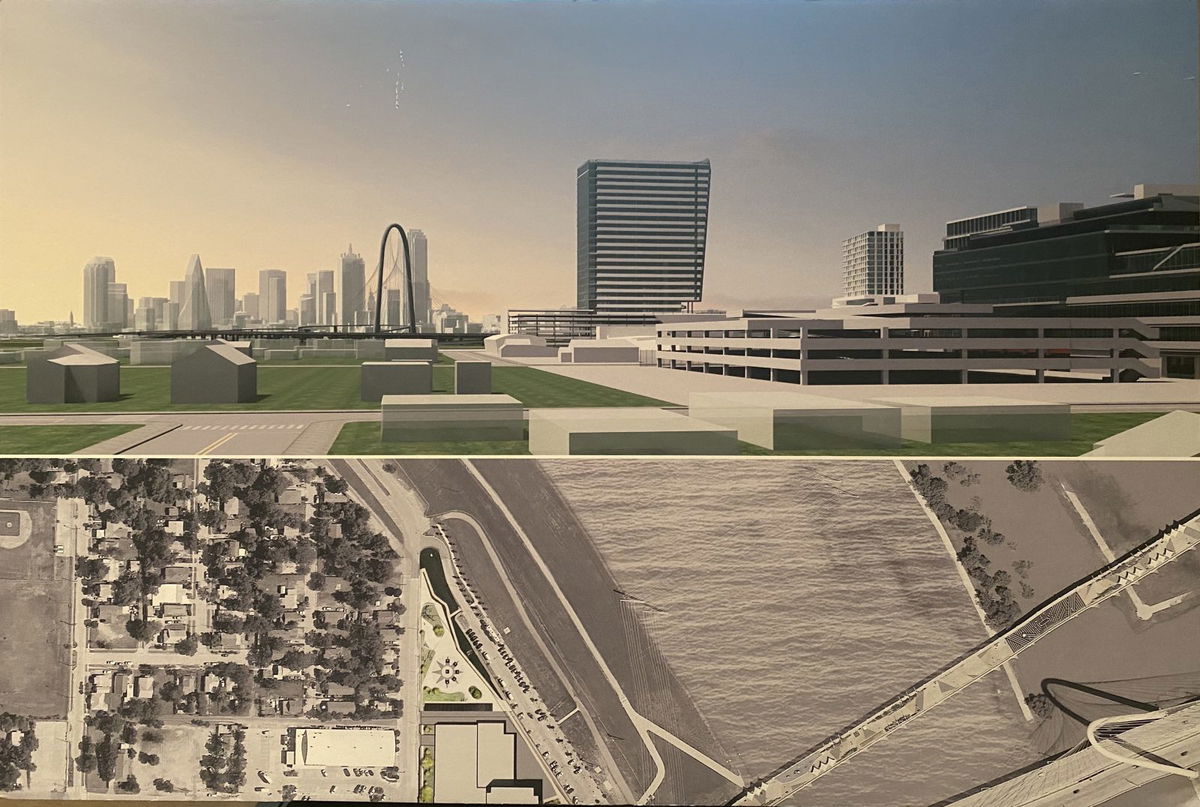

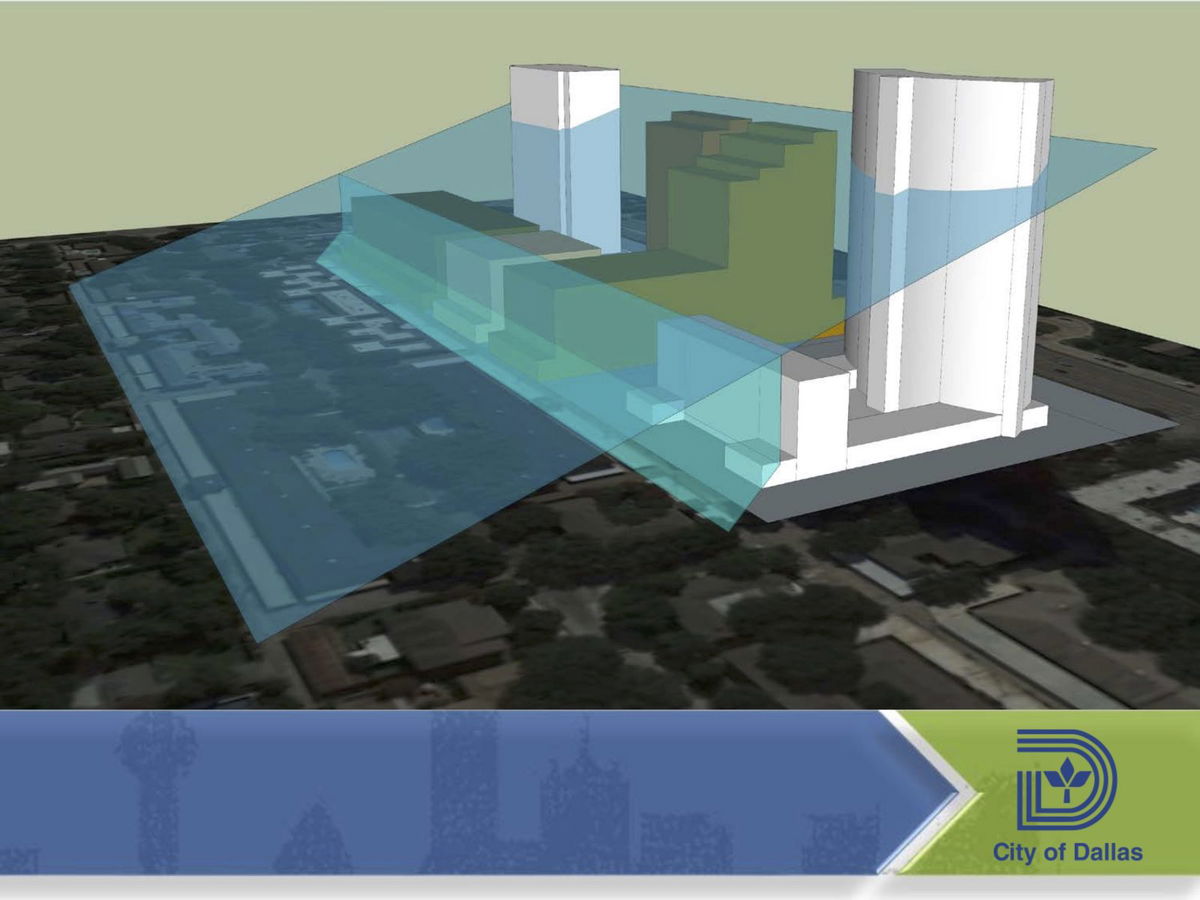

The three parcels at Gulden and Singleton — right at the base of the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge that connects West Dallas to Downtown — are the pièce de résistance of the developer’s holdings. On Thursday, the City Plan Commission will consider West Dallas Investments’ request to allow a 400-foot tower on the property with the hope of attracting a Fortune 500 company like Amazon, Google, AT&T or Toyota.

Such a tower would loom large, both literally and metaphorically, over a predominantly Latinx and Black neighborhood where the median income is $32,696. Essential workers abound in West Dallas, but their hard-earned incomes can’t handle the financial pressure of mushrooming property values and their corresponding taxes.

Longtime residents have always valued the quiet streets and beautiful views West Dallas affords, even as their neighborhood historically was devalued by government officials and business elites, despite its proximity to downtown. Finally, West Dallas’ worth is being recognized, but the quiet streets are now bustling with traffic, and the views slowly are being obscured.

Many residents fear that, soon enough, they, too, will disappear from the landscape. Their decades of investment in land no one else wanted, and a community no one else cared for, isn’t enough to compete with seasoned developers who have deep pockets, and a city wanting to turn “underperforming real estate” into a reliable source of tax revenue generation.

From their vantage point on the west side of the Trinity River, a 400-foot tower would be a pivotal domino to fall in the chain that leads to the end of West Dallas as they know it.

‘No matter what we do, it’s going to happen’

Jeannette Salazar lives on Bataan Street in West Dallas’ historic La Bajada neighborhood. As a 10-year resident, she’s relatively new to the area — her husband’s uncle, Gilbert Zuniga, who lives four doors down, has lived in West Dallas since the 1940s.

Zuniga used to own Gilbert’z Trucking on Bataan close to Singleton. West Dallas Investments now owns the property and is proposing to build an 8-story office building on the site.

Salazar remembers visiting Zuniga’s office and seeing images on his wall of what West Dallas would look like by 2030.

“Mija, this is what the future’s going to look like,” Zuniga would tell her. “No matter what we do, what we say, it’s going to happen. This is going to be a parking garage.”

Salazar’s family still owns five consecutive lots on Bataan Street. A number of houses in La Bajada are for sale, and one newly built home recently was advertised as being in “the heart of Trinity Groves.”

Salazar wanted to ask the Realtor, “Do you know anything about my neighborhood? I am not in Trinity Groves. Our neighborhood was established in 1929. Trinity Groves is restaurants and apartments in the La Bajada neighborhood.”

Some of her neighbors’ homes are selling for $200,000. The Salazars have been offered as much, and they aren’t biting.

“Give me $300,000 and we’re talking,” Salazar tells prospective buyers. “That’s what it’s going to cost me to go somewhere else in this county to buy a house and not have a mortgage payment.”

The response, she says, is crickets.

Proponents of redevelopment often point out that as gentrification occurs, longtime residents can cash out and make a handsome profit. But for those who want to stay, the sudden increase in property values gives them little choice.

The 650-square-foot home Ramirez inherited on Gulden, on a lot that covers less than a tenth of an acre, is now valued by the Dallas Central Appraisal District for $200,000 — eight times the property’s $24,500 value when she inherited it seven years ago. And her annual property tax bill has risen from $300 to $5,500.

“I would not want to sell,” Ramirez says, “but I’m going to be forced to move out at a price that isn’t going to take care of my kids and grandkids.”

Salazar says many of her neighbors are elderly and live on $1,200 monthly checks from social security.

“You’re pushing out that little person because they can’t afford it. ‘Oh, it’s just a Mexican neighborhood. They don’t matter,’ ” Salazar says. “What do you do? As a person who lives here, how much say do we really have?”

A ‘community benefits agreement’ hidden from the community

The first time Salazar caught wind of the tower was at a La Bajada neighborhood meeting in November 2019, when West Dallas Investments bought Thanksgiving dinner for residents and gave their presentation. The neighbors present indicated their support of the project, according to La Bajada’s board of directors.

Sixty property owners in the vicinity were sent mailers in late January 2020 letting them know about the rezoning request and asking whether they were for or against the change, which is a city requirement before a rezoning case goes before the City Plan Commission. Only one property owner responded, in support of the proposal.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit before the 400-foot tower proposal made it to the plan commission agenda, and it didn’t make an appearance until November 2020. In the months between, West Dallas Investments met with the seven members of La Bajada’s board several times to develop a community benefits agreement.

The agreement is intended to “preserve, enhance, conserve, and maintain the integrity and stability of the La Bajada community,” as the board pointed out in a letter it distributed to the neighborhood’s 300-plus homes in late November 2020. The letter includes a list of items West Dallas Investments agreed to support, such as “home repair assistance for La Bajada Residents” and “funding assistance and collaboration for community and cultural events.”

In return, the association agreed to support West Dallas Investments’ “two proposed development projects and their pending zoning cases,” — the 8-story office building on Singleton and Herbert, and the 400-foot, 28- to 32-story office building on Singleton and Gulden.

No one except West Dallas Investments executives, La Bajada board members and their respective attorneys have viewed the agreement. At a West Dallas community meeting Nov. 30, when neighborhood residents asked for it, Jim Reynolds noted that it is a “contractual agreement” that he is “not at liberty” to give out, but that the La Bajada board “can share as much or as little as they wish.”

Dallas Free Press followed up with Reynolds and La Bajada board president Maria Lozada Garcia via email, asking for a copy. Garcia responded that “it is not a document for public release as [West Dallas Investments] included the confidentiality clause” which the “board agreed to uphold.” She added that Reynolds offered to have the attorneys write “a summary document with all the important benefits and points,” and to “make the document available for review in his office for La Bajada residents/homeowners.”

The reason a legally binding agreement based on a public zoning request included a confidentiality clause, Reynolds says, is because “the City has NOTHING to do with the CBA. Obviously though, without zoning cases being approved by the City, there would be no CBA.”

“In all reality,” Garcia noted, “it is not a ‘true’ Community Benefits Agreement, but as Jim stated a ‘partnership’ agreement between La Bajada Neighborhood Community Association and West Dallas Investments for support of the zoning cases. A ‘true’ Community Benefits Agreement, as defined by the Community Benefits Law Center, would have been a coalition of all the neighborhood associations or non-profits being affected by these two developments.”

West Dallas has such a coalition — West Dallas 1, an umbrella group of neighborhood associations that focuses on education, environmental, and housing and zoning issues. At its most recent virtual gathering in early November, the coalition voted to oppose the zoning request for a 400-foot tower, despite the La Bajada board’s support of it.

“I respect the sovereignty of each neighborhood but have made it clear many times, in many conversations, that we have to work as one,” West Dallas 1 president Raul Reyes said on the call. “West Dallas, 75212, comes first. No one neighborhood is above West Dallas. If we have that mentality, that’s it — we gone.”

‘It’s Brooklyn looking into Manhattan’

West Dallas Investments’ final pitch took place on a night so cold that the planned outdoor meeting became a mask-wearing, chair-spaced indoor gathering at 3015 Trinity Groves, right across the street from the proposed tower.

“This site is very uniquely suited to attract corporate office users,” Laura Hoffman of Winstead, the law firm representing West Dallas Investments, told the 50 or so West Dallas residents gathered. She noted that her client was in conversation with Amazon, AT&T, Google and Toyota.

“If we want that kind of quality development that could be a game changer for this part of the city,” Hoffman continued, “that’s why this site is so important.”

West Dallas Investments owns nearly 9 million square feet of land south of Singleton. The presentation from Hoffman, Reynolds and Winstead’s Tommy Mann was designed to answer the question: Why here? Why build one of the tallest buildings in Dallas north of Singleton, adjacent to a historic residential neighborhood?

Mann noted that West Dallas Investments already has the zoning it needs to develop land south of Singleton. “The only zoning we’re asking for is here on the north side,” he said.

“Trust us — if we could have already built this for a tenant, we would have,” Mann said after the meeting. But just south of Singleton is an Oncor electric substation that would be “a very unattractive adjacency for a big corporate user,” he said.

Mann pointed to the future Harold Simmons Park, Trinity Groves restaurants, the view from West Dallas to downtown Dallas. As District 6 Plan Commissioner Deborah Carpenter put it after the meeting:

“It’s Brooklyn looking into Manhattan.”

Eduardo Rodriguez, the owner of Cedar Crest Gardens on Singleton, attended the meeting and pressed West Dallas Investments on why they couldn’t choose a different spot that wouldn’t erase the iconic skyline for longtime residents. After the meeting, he shared a photo of what he sees on his daily drive along Singleton toward the river.

“I don’t want that photo to be history,” Rodriguez said.

During the meeting, Hoffman pointed to city plans showing that the land and Gulden and Singleton was suited for a tower. Both the Trinity River Corridor Comprehensive Land Use Plan from 2005 and the West Dallas Urban Structure and Guidelines from 2011 include that vision.

The guidelines’ primary objective, however, is to “enhance and protect La Bajada.”

‘Things were promised to the neighborhood’

The longstanding position of the West Dallas neighborhood is that developers have all the entitlements they would like for land south of Singleton, says James Armstrong, who chairs the coalition’s housing and zoning committee.

But north of Singleton, residential zoning includes a “proximity slope” to protect single family homes from having to be right next to tall buildings. Armstrong says that even though West Dallas Investments says they can build up to 200 feet with the site’s current zoning, that number is really only 115 feet because of how close the property is to homes on Gulden, such as Connie Ramirez’ house.

The other issue, Armstrong says, is that “initiatives and community support programs were supposed to be in place before big development came, especially north of Singleton.”

“Things were promised to the neighborhood that would protect the neighborhood, that would prevent gentrification,” Armstrong says. “The city and the developer have not followed through on their word to protect La Bajada.”

West Dallas Investments tried to reassure neighbors at the Nov. 30 meeting that their community benefits agreement includes working with the Dallas Central Appraisal District and the Texas Legislature to try to limit property value and tax increases.

“What guarantee can you give me that my taxes won’t go up?” someone asked. “I’m not leaving my neighborhood.”

“I can’t guarantee it because we don’t appraise the properties,” Reynolds replied. “But whether we do these projects or not, taxes are going to continue to rise, and not just in West Dallas.”

“Zoning in and of itself has no impact on what your property is valued at,” Mann agreed.

The West Dallas residents in the room were not convinced. At the close of the meeting, District 6 Councilman Omar Narvaez told the room, “This isn’t done, and I want to know if it’s worth working forward or not.”

He asked for a show of hands of those who supported the project. A single table, where the La Bajada board of directors were sitting together, raised their hands. When Narvaez asked who opposed the rezoning, the rest of the room raised their hands.

West Dallas Investments has two more hoops to jump through to get its zoning — the City Plan Commission meeting tomorrow, and the subsequent City Council vote. Commissioner Carpenter has said she’ll prioritize the opinions of La Bajada neighbors who live closest to the site. Even though Salazar, Ramirez and other neighborhood residents oppose it, the board is officially behind it, and the single response from property owners in the vicinity indicated support.

“As the city grows, community leaders have learned that we as residents can no longer afford to sit in the comfort of our homes and remain uninvolved,” the La Bajada board of directors wrote in its letter to neighbors. “Doing so, we silence our own voice and give away our power to those few involved.

West Dallas 1 is rallying opposition after being caught off guard by this week’s vote. The zoning case is listed on the agenda as “under advisement,” but a city spokeswoman says that’s because “it was held at a previous hearing and is not a new case.”

Salazar isn’t optimistic about the vote.

“As a regular person, sometimes it doesn’t matter what we say. Money’s gonna talk, and they’re going to do what they want anyway,” she says. “I feel for all these old people who have been here for years. People are tired of it. It’s getting too expensive with taxes. They’re going to be taxed out of their homes. I don’t want to leave but if push comes to shove …”

Ramirez believes whatever is meant to be will be. She hopes, though, that if a tower is meant to be across the street from her godparents’ house, that when the offers come to buy her property, ‘they will give us something that we will not have to worry.’ ”

To weigh in on this zoning proposal, contact District 6 Councilman Omar Narvaez at 214.670.6931 or omar.narvaez@dallascityhall.com.

Leave a Reply