Julie Saqueton is looking forward to the end of the pandemic for a lot of reasons. She’s ready to get back to hosting girls’ nights out and senior field trips in person, along with the other community services St. Philip’s School & Community Center provides in South Dallas.

She’s ready to get back to giving people choices.

Saqueton is the chief community advancement officer at St. Philip’s, which runs Aunt Bette’s Community Pantry inside a small, efficiently run building that used to be a liquor store, inconveniently located next to the facilities where St. Philip’s would host after-school programs. St. Philip’s took over the building in 2015 and expanded their limited food box distribution to a fully operational client choice food pantry, lined with tidy shelves stocked with breakfast cereal, condiments, and grains. A refrigerated section along the back wall houses the produce, meat and dairy.

“We were able to acquire this building and turn it into a dignified shopping experience,” Saqueton says.

Patrick Stevens, 53, rides a bike to the pantry, which he calls a “blessing.” He can barely walk, and making the mile trek to the pantry twice a month used to take hours. The folks at St. Philip’s noticed and surprised him with a bike. While choice wasn’t his primary concern, Stevens noted that it’s nice to have.

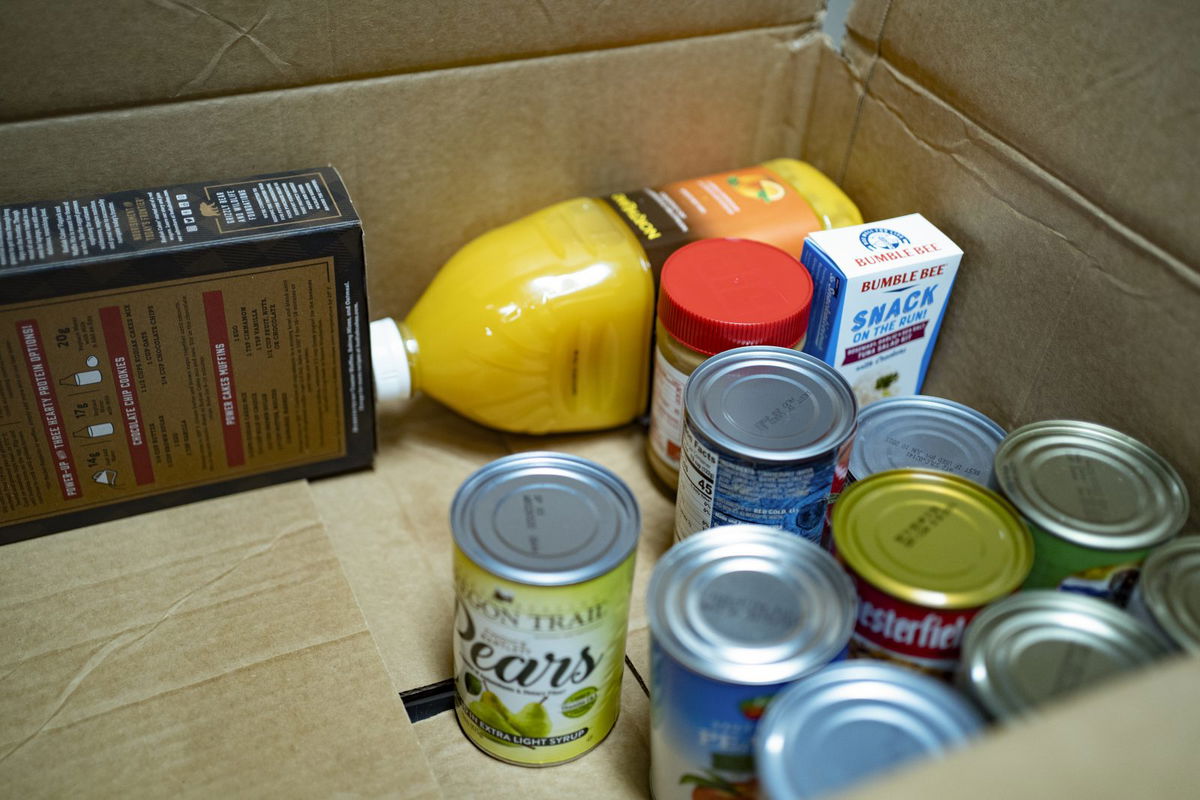

“You got the variety of food. Meats. Canned goods.” Stevens says, referring to how he shopped at Aunt Bette’s before the pandemic. “You went around and you got to choose.”

Not only did Aunt Bette’s have the basics but the pantry also had some of the more specific items he needs, like Ensure.

In non-pandemic times, St. Philip’s 750 family clients come in during an appointed shopping time, choose their groceries, and go to the checkout counter just like they would at a retail grocer. Instead of cash, the clients’ groceries are deducted from their bi-weekly allotment of food — a calculation based on the size and composition of their household.

Stevens may not have been conscious of the effect, but by laying out the pantry like a grocery store and offering choices to hungry neighbors, experts say choice-based food pantries create the kind of positive psychological environment conducive to healthy consumer habits. This emerging trend of choice in food pantries is turning into a best practice.

During the pandemic, the team had to shift their distribution model, moving to a pre-bundled food box drive-through. They’ve been operating in an emergency model, Saqueton explains, which opens distribution to people outside their client-base in zip codes 75210 and 75215. Anyone who drives up can get a box. The pandemic put a vice-like squeeze on families, so Saqueton was glad to be able to help as many as possible, but she was sad to see the shopping experience change. She’s ready to get people back to selecting the food they want — food they will prepare, eat and enjoy.

The North Texas Food Bank, Aunt Bette’s primary supplier, considers the pantry an exemplar. Client choice pantries minimize waste, advocates say, because people aren’t given food they can’t eat or don’t know how to prepare.

“[Aunt Bette’s] was one of the first collaborative efforts with the food bank to build a model pantry,” says North Texas Food Bank community partnership specialist John Murray, who manages St. Philip’s program. The food bank and Toyota consulted with the pantry to streamline the space and create a system that would minimize wait times and keep storage and operations from spilling out into the shopping area.

“It gives the client the feel of worth,” Murray says. “You’re not just herding them through like cattle. What you’re providing for them is more than just food, but to say to them, ‘You’re another human being, so we’re going to treat you that way.’ ”

Offering choice also might be helping Aunt Bette’s shoppers walk away with healthier food in hand.

In the Journal of Consumer Research, Daniel Mochon explored what he called “single option aversion.” He found that when given only one option, consumers were highly likely, around 90%, to pass on that option and search for a better one elsewhere. While the experiment didn’t account for the added incentive of Aunt Bette’s groceries being free, it does show that when only one option is given, it tends to diminish a shopper’s investment in the choice.

No strategy has entirely overcome the appeal of junk food or the time and money it takes to purchase and prepare delicious home cooked meals, but personal investment of choice-making seems to be essential, says Yale researcher Zoe Chance. She has studied various efforts to entice people to eat healthier, everything from limiting options to increasing options, from education to incentive programs. Some strategies — researchers call them “nudges” — work better than others to make healthy options more appealing.

The national food bank chain Feeding America partnered with Cornell University to study the effect of nudging food pantry clients while giving them choice. Nutrition information and the appealing display of food around the store increased the likelihood that food pantry clients would choose healthier foods by 46%.

What they didn’t do was take away all unhealthy choices. Maintaining the element of choice is inherent to most successful nudges in most contexts.

In any health-related situation, heavy pressure — including limiting choices — can cause people to respond emotionally — and negatively. Psychologists call this “reactance.” Reactance is like anger or defiance, and it can be seen in debates about mask mandates, vaccine passports and even Google’s ill-fated “meatless Monday” initiative.

When a choice is made freely, Chance says, “Your whole thought process changes. It’s less of an emotional decision and more of a cognitive one.”

That cognitive investment can pay off. If a person feels invested in their choice inside the food pantry, they are less likely to seek other options. In neighborhoods like South Dallas, the most accessible alternatives are convenience stores or fast food restaurants.

The earlier in the decision making process clients can be involved, the better, Chance says. In a grocery situation, that means deciding what appears on the shelves.

That’s tough for a food pantry, which is limited in the choices it can offer because they rely on donations. Aunt Bette’s shelves are stocked by the North Texas Food Bank and donations from retailers like Kroger, Walmart and Target. As those stores left the community, they increased their donations to food pantries in the area, Murray says.

With retail donors, Aunt Bette’s has less control over what comes in.

“We get more than we need of cakes and breads,” Saqueton says, “but there’s some fun having new stuff every now and then.”

Aunt Bette’s has more say in what comes from the North Texas Food Bank, which allows the pantry to control its inventory. An iPad-toting volunteer accompanies each shopper through the pantry, noting their preferences and dietary restrictions, and, when possible, accessing shared health information to find recommended nutrition options. The software isn’t perfect on the last component, Saqueton says, but it’s coming along.

The software allows Aunt Bette’s to, like a grocery store, stock more of what clients want and less of what they don’t.

“If no one in the neighborhood likes black beans or pinto beans, let’s not keep getting them,” Saqueton says.

At Brother Bill’s helping Hand, which operates a client choice food pantry in West Dallas, director of operations Courtney Cuthbert saw an immediate difference in clients’ food intake once the pandemic pushed Brother Bill’s to a drive-through model, similar to Aunt Bette’s. Their clients simply weren’t eating some of the food in the boxes, and returning them instead.

When they could come into the pantry to shop, Cuthbert says, not only would they select what they liked, but recipe cards and taste tests exposed clients to new foods, like spaghetti squash, that are unfamiliar but actually quite easy to prepare. Nonprofit partners would tailor cooking demos to the healthy foods the pantry was trying to promote.

“They’re willing to try it if they know how to fix it,” Cuthbert says.

Research supports what Cuthbert is seeing, says Tara Cristobal-Rivera with the Center for Nutritional Psychology.

“It’s not only having choice, but giving people the education on what to do with that choice,” Cristobal-Rivera says. “It’s not necessarily prescribing a specific diet … it’s about providing education and awareness about what these foods can do for you.”

Aunt Bette’s and Brother Bill’s emphasize balanced meals but give clients control over each component. Carol Morton is a client at Aunt Bette’s, and while she likes the drive-through model more than the shopping — she says she gets more per box, and it’s faster — she did like the ability to put together her menu the way she wanted it. Morton, who lives by herself, says she would choose ground meat and beans, and make a huge pot of chili that she could eat over a few days.

“When we were going inside, we got a full meal. We could cook a full meal. Like the canned vegetables and stuff like that,” Morton says. “And, I liked that.”

The combination of choice and education is critical, Cristobal-Rivera says, in helping clients go from experimenting with healthy food, to forming healthy habits within their current routine, to adopting a healthy lifestyle that can withstand changes to routine. Some studies show promise when nutritional coaches make monthly check-ins to troubleshoot with food pantry clients, whose healthy habits are bumping up against the realities of harried schedules, resistant kids and anxiety.

Right now, research shows that choice and education increase food pantry clients’ commitment to healthy eating in the short term, but more research is needed on the long term effects.

This story is part of a project on potential solutions to food insecurity in the neighborhoods of South Dallas and West Dallas. It’s reported through a partnership of the nonprofit Dallas Free Press and The Dallas Morning News, with support from the Solutions Journalism Network. For more information, email info@dallasfreepress.com.

Leave a Reply