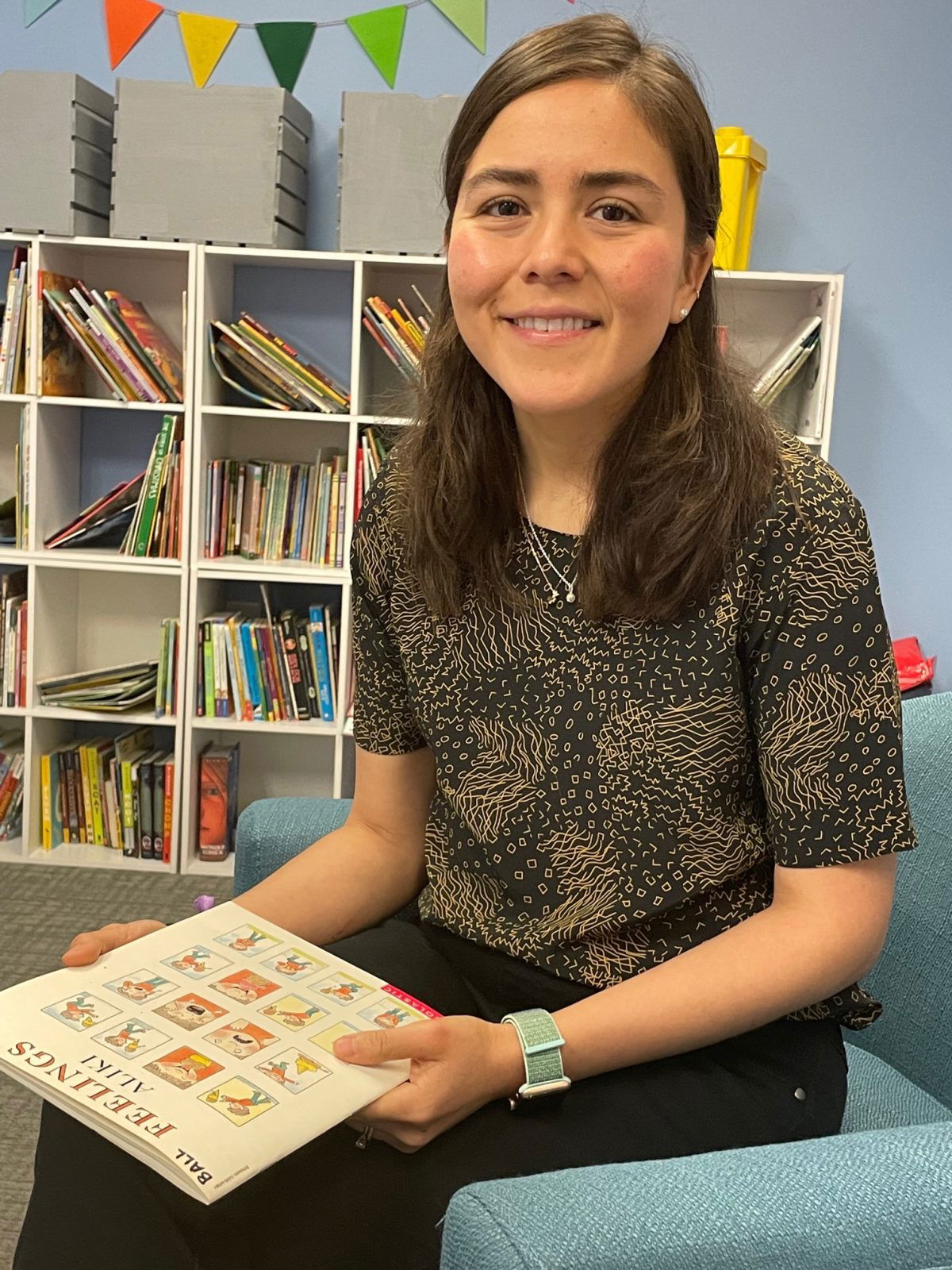

Clinical psychologist Mara Estrada is preparing to see her third client of the day at Brother Bill’s Helping Hand in West Dallas. She sets up her laptop in the mental health care office. Children’s books line the shelves behind her.

Since the pandemic, Estrada sees about half of her clients online.

“We were all going through communal trauma and communal anxiety,” she explains. “The trauma that was stored for a while, the pandemic brought to the surface.”

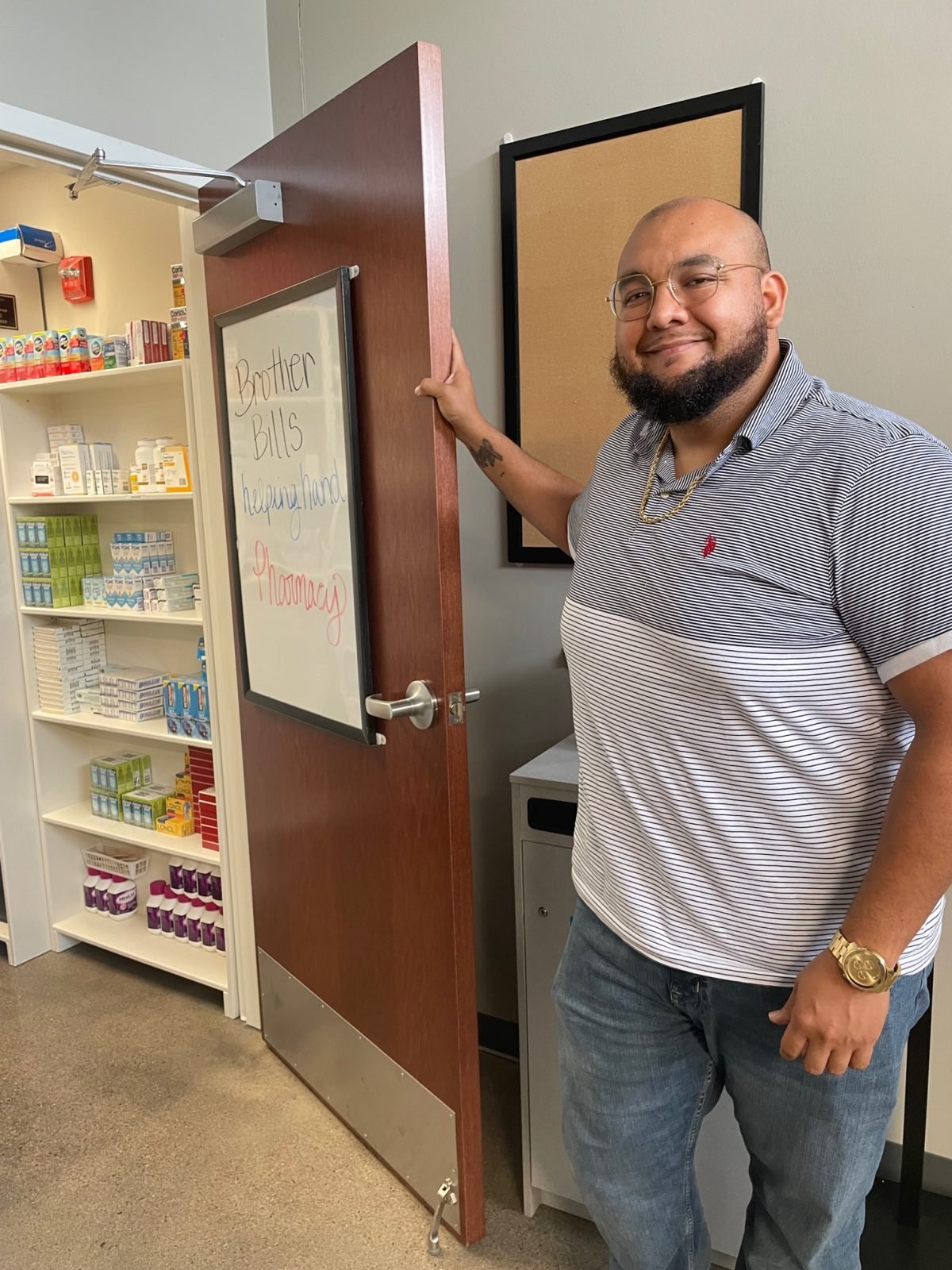

Brother Bill’s Helping Hand has been providing free mental health services for this predominantly Latino neighborhood since 2014. Prior to the pandemic, says clinic director Ivan Esquivel, they typically had about 500 visits a year. Last year, they had 1,600.

“There was a health crisis happening, right? So, we flipped to telehealth,” Esquivel says. “What we found out was we were meeting them in their homes, and we started seeing more people because they knew they wouldn’t have to come in.”

The increase in mental health services for depression and anxiety mirror national trends. However, Esquivel says he was surprised at the increase of Latinos seeking out mental healthcare at Brother Bill’s because it is still considered taboo in the Latino community.

“These communities are very tight. Everybody knows. So, there’s always that shame,” he says. “It’s been instilled in us since we were children. If you talk about mental health, you’re weak.”

Finding ways to overcome this cultural hurdle isn’t easy, but Estrada says seeing patients online has helped. She says she can see clients on their time — adults don’t have to leave work and children don’t have to leave school.

“We’re working a lot with schools. I have to ask for permission to use a classroom. [A student] can bring their tablet, and they can go back to class after the session.”

In West Dallas, about a quarter of the people live below the poverty line, according to Healthy North Texas. Transportation, food and healthcare are not guaranteed in the 75212 zip code. So, finding innovative ways to meet the community’s needs has always been part of Brother Bill’s mission. The nonprofit has been working in West Dallas for more than 75 years.

“These communities are impoverished. Brother Bill’s is in the middle of a food desert, the closest place to even get fresh food is over a mile away at Walmart,” Esquivel says. “There’s just so many barriers for these families.”

Often, when a person comes into Brother Bill’s, they will end up receiving help in different areas of their lives.

Brother Bill’s core programs include a free grocery store, where neighbors have access to healthy food; access to health care for the uninsured; and education programs that include English classes, computer courses and fitness programs.

One of Estrada’s clients is a 10-year-old girl. When her father came to the clinic, he was deeply concerned because she was sleeping under her bed. The girl’s mother recently had left the home, and her father worked all of the time.

“She spent all of her time under the bed, and that was a depression sign. She just wanted to sleep and she just wanted to eat, but there was no food at home,” Estrada says. “When her dad would come home, they would go to CiCi’s pizza every day.”

Estrada says she focused on psychoeducation for the girl, but also on helping her build life skills.

“That Mom left is not your fault,” Estrada explains. “We have to work on that trauma. We have to work also on daily skills.”

Estrada used the kitchen at Brother Bill’s to teach the girl to make simple, healthy meals. The family also signed up to start receiving free groceries from the store.

“She was getting so excited because she’s learning new skills, and she’s feeling empowered,” Estrada says. “She’s feeling equipped.”

The mental health clinic lost a counselor earlier this year, and now has only two therapists. Estrada is the main person that people see. The funding for Estrada’s position is set to end in 2022. Esquivel says Brother Bill’s will do everything in its power to keep Estrada on staff. He says she has built a lot of trust in the community, and that cannot be easily replicated.

“In [Latino] communities, it’s all about trust,” Esquivel says, “We serve 91 zip codes. They know Mara. They know our community. That trust factor has a lot to do with that.”

Most clients see Estrada for about 20 sessions, but even though Brother Bill’s has a waiting list of about a dozen people, Estrada says her clients are always welcome to come back.

The 10-year-old girl and her father continued counseling for several months, but then stopped. However, the girl recently returned.

“We always leave our door open,” Estrada says.

Brother Bill’s partners with The Center for Integrative Counseling and Psychology to provide therapy to clients in need. The Center created the Partnership for Accessible Counseling and Training (PACT) in 2014. They now have 11 PACT partners in 13 locations. Brother Bill’s is one of three in West Dallas; the others are Wesley-Rankin Community Center and West Dallas Community School.

To make an appointment, contact the PACT program. The Center can be reached at 214.526.4525.

Leave a Reply