The noisy renovations at the house next door aren’t getting in the way of 15-year-old Daija Showers’ school work. Her eyes are glued to her laptop as she stares down her geometry.

“It’s kind of hard, but I will get it … eventually,” she says. “I find school very important to me because of the road that I want to take.”

Daija wants to be an attorney. She was concerned about how being an at-home learner as a freshman at Lincoln High School would impact her studies, but her mom didn’t want to take any chances with COVID-19. Daija’s younger brother is undergoing chemotherapy for a mass near his lung. They have been virtual students for the entire 2020-21 school year.

“I found it hard at first with the complications of the computer, but I got used to it.”

In January, Daija became one of the first Dallas ISD students to test a new way to access the internet at home. Only 50 students were in the pilot program.

Dallas ISD built a large cell tower on Lincoln High School’s campus to extend the existing WiFi signal to homes within a two-mile radius of the school so students and their families could access the internet for free. Daija lives just three-quarters of a mile away from Lincoln. She’s had a mobile hotspot, but says the internet is so much better with the new wireless network.

“It’s faster,” she says. “It goes through things quicker with no interruption.”

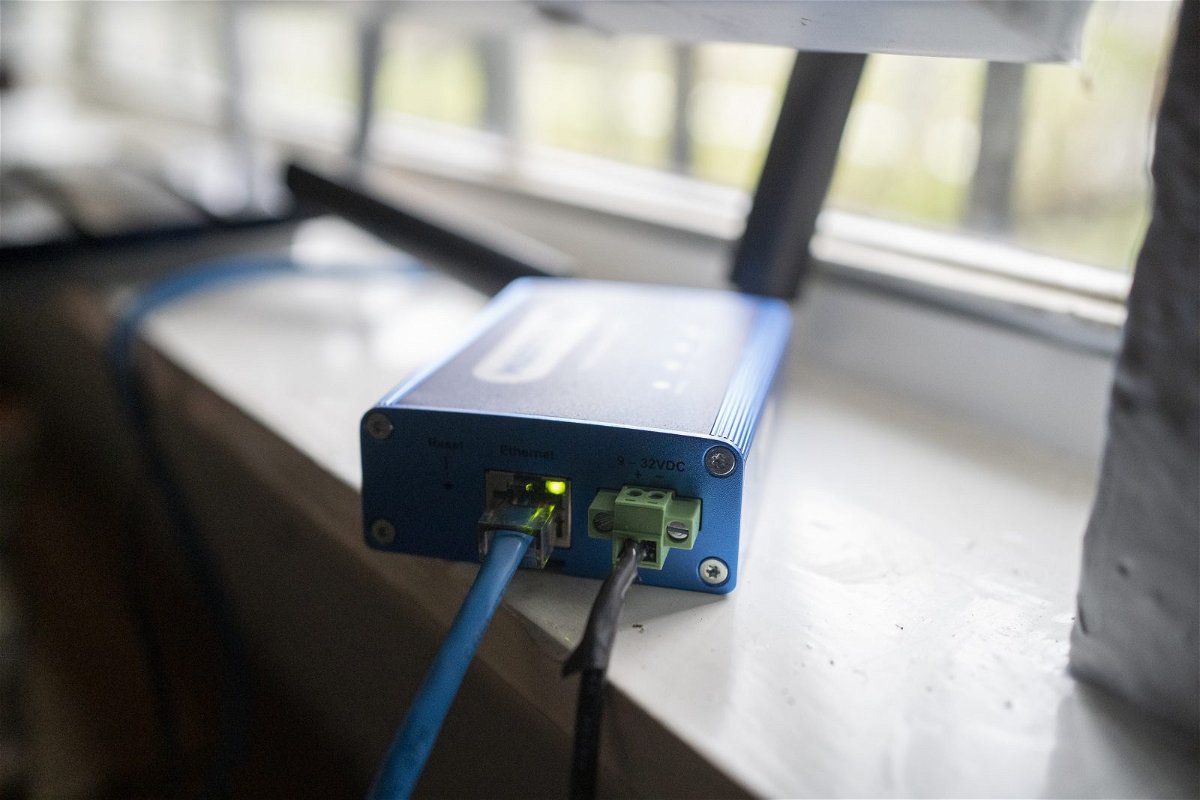

A small box sits on the window sill facing in the direction of the school. Daija says all she had to do was plug in some cords and type in a code. The receiver grabs the new cellular signal from the tower and converts it into a Wi-Fi signal for the house. Now, she can jump on the internet whenever she wants.

“It’s just ready to go and automatically connects,” she says.

Daija’s brother, 11-year-old TeQuan, stumbles into the room looking for his computer. Yesterday was his birthday, and he stayed up late playing video games. Learning from home has been especially difficult for him. He’s a fifth-grader at Charles Rice elementary school. His mom, De’siree Showers, says the school was not helpful when his son was having internet problems.

“If a kid is having problems at home with their internet, [the school] kicks them out [of the zoom call] and marks them absent,” Showers says. “How’s he going to learn?”

Showers was surprised when she received her son’s report card showing the number of absences and missing work. She reached out to the school and worked out a deal where TeQuan could skip his live Zoom classes. He is still expected to complete his school work.

Now, with the new private network system, Showers says her son is able to log on easily from home. Daija says it’s made a big difference for both of them.

“Since we are able to have a faster WiFi, he is able to get his work done quicker,” Daija says. “Everything gets done when it’s supposed to.”

How it works

Dallas ISD Chief Technology Officer Jack Kelanic says he is optimistic this wireless network plan can help thousands of students in the Dallas school district. Over the last decade, the district has invested to ensure that each of the 230 campuses has internet service. Kelanic says adding the cellular towers allows the district to leverage the existing investment and expand internet access to homes within a two-mile radius of the campus.

“It’s the same service that they would get on campus, they are just getting it at home,” Kelanic says.

However, early tests at Lincoln show that the cellular signal is not reaching all of the students in the two-mile radius, so the district is investing in constructing more cellular towers on schools close to Lincoln to extend the signal. The additional building costs are still within the district’s budget for the pilot. Construction will begin at Charles Rice and Dunbar elementary schools this month.

“I think it’s a good lesson learned for us,” Kelanic says. “The more infrastructure you have, the better.”

In Dallas, the plan is costing roughly half a million dollars in infrastructure for each of the five high schools (Lincoln, Spruce, South Oak Cliff, Pinkston and Roosevelt) in the pilot program. The school board authorized $4.5 million for the pilot. The district just gave the go-ahead to start constructing the cellular towers for South Oak Cliff and Roosevelt high schools.

Dottie Smith, executive director of The Commit Partnership, a nonprofit dedicated to creating an equitable education for all North Texas students, says those upfront infrastructure costs are one-time capital expenses.

“Part of the reason we are excited about this is because the long-term costs feel very sustainable,” Smith says. “And, maintenance is looking like it’s not going to be more than what the districts are paying for hot spots.”

Smith says when the pandemic hit, more than 75,000 Dallas County students didn’t have access to the internet at home. The quickest, most reliable solution to get students connected were hot spots, but the technology is expensive and not financially sustainable.

While the upfront infrastructure costs for a private wireless network are more expensive, the monthly costs are significantly less. That’s because districts pay internet service providers like AT&T and Spectrum a monthly subscription fee for the hotspots.

“So, you know, as opposed to a hotspot subscription where you may pay $30, $40, $50 a month, and it’s going to escalate over time, [the cellular network] has some one-time upfront costs, but then the ongoing run costs are pretty low,” Smith says. “So, if the network performs the way we expect it to perform and we can really, you know, reach as many families as we need to reach, I think it has great potential to take to scale.”

Students served One-time cost MRC Total Mobile hotspot 1,000 $75,000 $25,000 $1.6M Private cellular network 1,000 $300,000 (infrastructure) +

$300,000 (user equipment)$2,500 $750K

Kelanic says there are other benefits to the wireless network. Dallas ISD is experimenting with a “repeater” that can be added to an apartment building to extend the signal to several students in a concentrated building. “There’s new equipment options coming online all the time. All we need is to mount the equipment somewhere on the building and that will further amplify that signal to make sure that we’re providing good home coverage for those kids.”

The district plans to add 200 more students to the pilot project at Lincoln before the end of April. The swiftness and sustainability are reasons the private wireless network plan is gaining steam for urban school districts everywhere. San Antonio ISD is working on a similar plan, as are Garland and Grand Prairie ISDs. Kelanic says he’s had conversations with Los Angeles as well as other districts in California and Utah.

“So, I think you can expect to see more of this type of solution within the state as well as nationally going forward,” he says.

Challenges for the pilot program

Lincoln High School freshman Tevin Ferguson also was tapped for the pilot program, but he hasn’t been able to participate. Ferguson has moved three times in the last six months because of his mom’s health and financial reasons. He’s currently living in Mesquite and sharing his cousin’s hot spot.

“Sometimes, I have problems when I’m in class. It will be the screen. It will shut down and stop working.” Tevin says it can be very frustrating. “Like make me mad-type frustrating because you can’t keep up.”

Ferguson’s mom, Sigrid Roberston, says she doesn’t know if the problem is the internet or something else. She has a newborn and suffers from Lupus. This school year has been extremely difficult.

“Last week, Tevin logged on — nothing. Every day there’s a problem,” Roberston says. “There’s only one teacher that my son does Zoom with. The rest of them, we can’t get in touch with. I don’t know if it’s due to the WiFi? [The school] is frustrated because we keep asking questions, and they really don’t have the answers.”

Kelanic says building the infrastructure has actually been the easy part. Connecting families is much more difficult, “you know, making sure we have the right messaging for families and working through all of the different, competing priorities that a campus may face.”

Smith agrees and says looking for ways to improve communication is something districts across the country are struggling to figure out.

In a couple of cities, Smith says philanthropists have offered vouchers to pay for internet at home for students, but only 15% to 30% of families have taken advantage of the option.

“How do we better understand what’s happening on the ground and why families may or may not be sort of hammering to get this service?” Smith asks.

That’s the next step, Smith says. Internet for All, a Texas-based coalition, is working with a consulting firm to look for ways to better improve communication and messaging, specifically in disinvested neighborhoods.

Post-pandemic internet needs

While the expectation is most, if not all, students will be back in the classroom in fall 2021, Smith says hybrid learning is here to stay.

“It’s sort of like part of a broader strategy. I think especially with there being a big push for in-person learning in the fall that we don’t lose sight. We don’t relax, and say, ‘OK, we don’t need to solve this anymore.’ We still do.”

Prior to the pandemic, the Pew Research Center had released research about the homework gap, which revealed that Black students in particular did not have access to the internet at home required for their homework.

“Because of the racial inequities with the internet and everything else, it’s just going to be even that much more important that this is a mainstay when we think about the backpack of supplies that kids need to have to be successful at school. That backpack has to have the internet in it,” Smith says.

Kelanic says creating wireless networks does look like a proven solution to provide internet for students who don’t have access at home. However, it also creates new questions about a school district’s responsibility for who gets this service.

“This type of approach has legs,” he says. “Should we approach this as a more targeted tool that we use for specific neighborhoods and communities that are underserved with internet infrastructure, or would it make more sense to do this at kind of a macroscale and go district-wide? So that’s something that we are analyzing right now, and trying to figure out what makes the best sense.”

This story was co-published by our media partners, KERA and the Dallas Weekly.

Leave a Reply