Co-published by our media partner, KERA. Listen to the radio version on KERA’s website.

Audra Brown stands on her front porch holding her 2-year-old granddaughter, Toya. Her four grandsons are inside their home in the Buckeye Trail public housing community in South Dallas’ Bonton neighborhood.

“They are playing on their tablets,” Brown says. “Just some games that the tablet came with.”

In the spring, as COVID-19 began to spread, the boys’ school, J.J. Rhoads Learning Center, pivoted to virtual learning. Brown didn’t want her grandsons to get behind in school, so she started paying $46 a month to AT&T for broadband. But she couldn’t afford to keep it up.

“I got behind on a couple of bills so I feel like the internet can hold off,” Brown explains. “We pay lights and rent and I don’t want to get behind on nothing.”

J.J. Rhoads principal Chandra Macklin says almost all of her students are from low-income households. She understands that internet access is a luxury that most families in her school can’t afford. But now it’s turned into a necessity. Her students have made huge advances in the last two years, and she doesn’t want them to regress. So in the spring, she made sure her families knew to pick up portable hotspots. These are small devices that students can use to connect to the internet from home.

“Connectivity is important now. This is how we communicate,” Macklin says. “So, if that meant that some teachers would even go home to help a parent get online — what we did was, how can we make sure that our students are still learning?”

“I didn’t know how to use this stuff so I called the school, and there was always someone there who could help me,” Brown says.

Macklin says she’s thankful that the school district was prepared with hotspots so her students could access the internet from home.

“I will say that I’m grateful for our superintendent and his foresight and the way that he sees things,” Macklin says. “How he projects to the future about what’s going to be needed.”

Investing in disinvested neighborhoods

Dallas ISD Superintendent Michael Hinojosa says that when the pandemic began and the district closed campuses, he had to make sure he could get his students online quickly. Hotspots were the fastest way to do that.

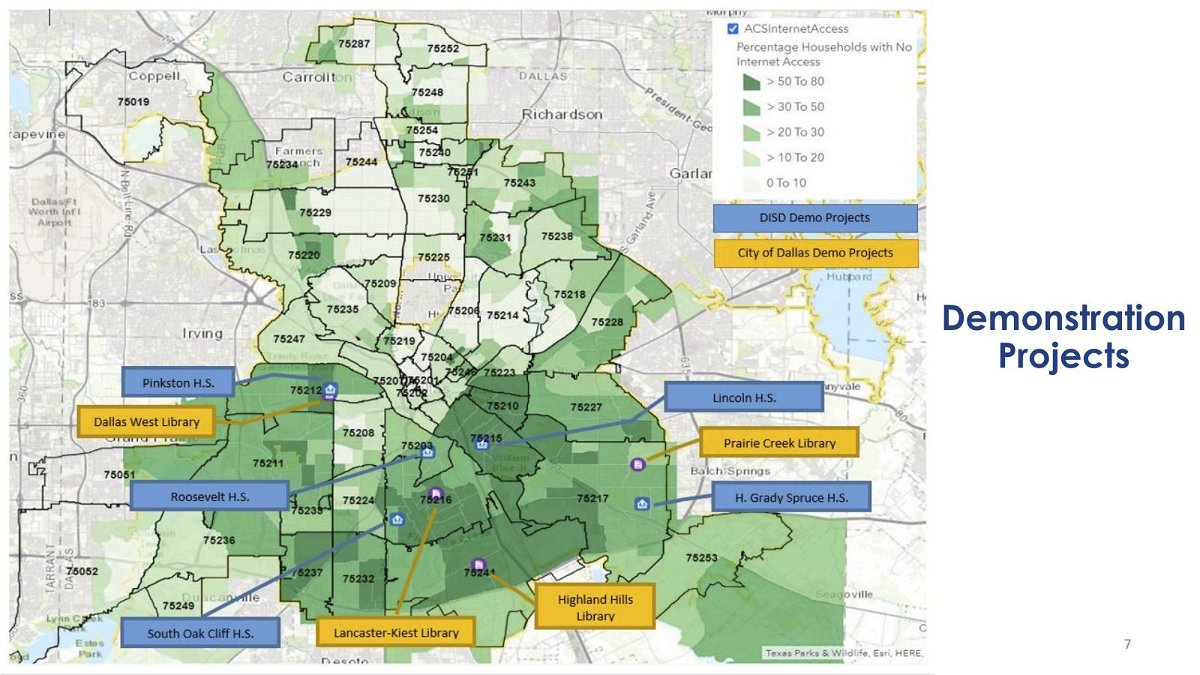

But Hinojosa wants a more permanent solution to the lack of internet access for Dallas ISD students — particularly those in South Dallas and other historically redlined neighborhoods.

“The same places that don’t have broadband are the same places that don’t have a Starbucks. They don’t have a grocery store,” Hinojosa says. “It’s the same places where you have high crime rates. So, all of these things are tied together.”

Texas State Senator Royce West says this isn’t a new problem.

“This issue has been going on for well over 20 years,” West says. “When you begin to overlap the census tracts that have the highest incidents of poverty, unemployment, criminal justice related issues, there’s a positive correlation between the two.”

West says the lack of proper infrastructure in Dallas’ southern sector limits people’s access and their potential.

“The fact is that you cannot function in this world anymore without connectivity.”

If it works for businesses, why can’t it work for schools?

Jordana Barton works for the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Like millions of Americans, she started working from home full-time when COVID-19 hit.

“We are all working from home since March, right? I was working on my virtual private network of the FED,” Barton explains. “I get a computer and access to the virtual private network through my little code that I put in and, you know, that’s how I access the internet.”

As she typed in her code one spring morning, Barton had an “a-ha” moment. For years, she had been studying the digital divide and its impact on low-income communities in Texas. Now, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, her work was receiving more attention. Cities were searching frantically for solutions as the need for reliable internet access became essential, especially when it came to virtual learning.

“I was no longer having to explain that this is a problem,” Barton says. “So, I was working on my virtual private network and I said, why don’t we give this to students? It is an enterprising solution. Why should it only be businesses that get this opportunity?”

The Fed, like a lot of large companies, has its own private wireless network, connecting employees to a central tower. The signal travels — uses public infrastructure — from the tower to other contact points, until it reaches the employee’s home.

All Dallas ISD campuses are equipped with wireless internet that staff and students could access while inside schools. The idea would be to take that same signal and send it to students’ homes.

South Dallas’ Lincoln High School, for example, could place an antenna on its roof and transmit broadband signals to household receivers. A student could then type a code into her laptop and sign on to the network from home.

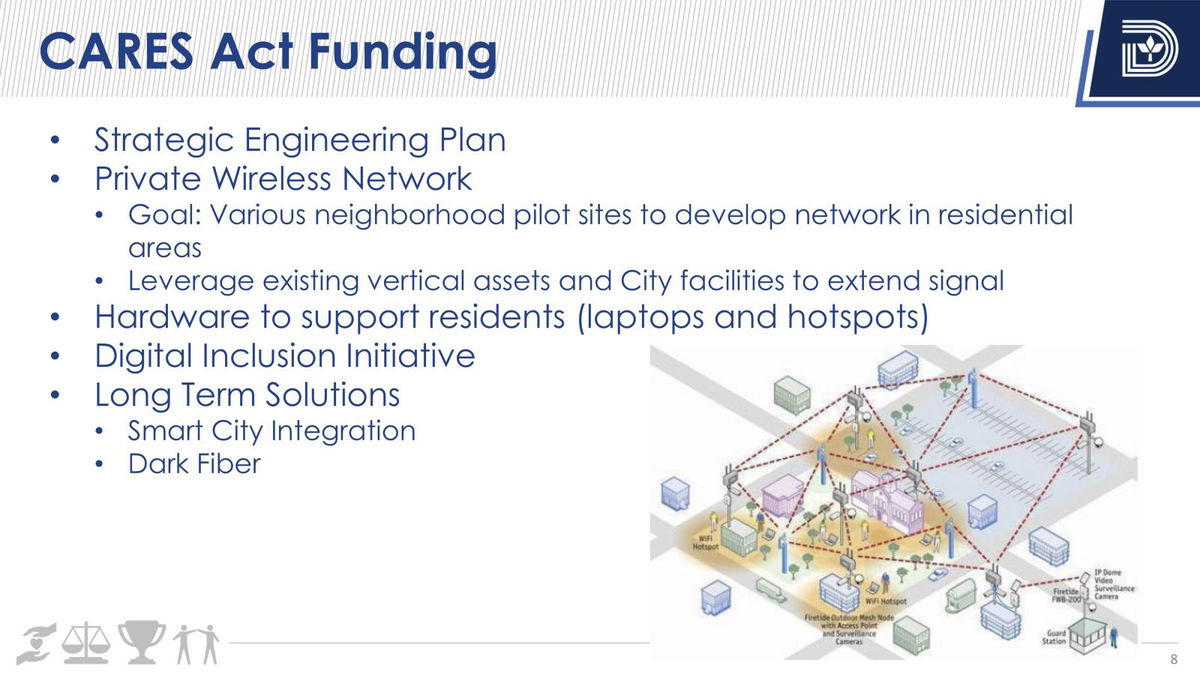

“You’re investing in this one-time as far as the capital expense. It’s a one-time cost,” Barton explains. “And you are paying for it with CARES Act or philanthropic funds to solve this huge gaping problem.”

San Antonio sets the pace for internet connectivity

The federal coronavirus relief bill gave state and local governments money to cover costs related to COVID-19 between March and December of this year.

In June, San Antonio became the first city in Texas to adopt Barton’s plan. The City Council approved $27 million to connect 20,000 students in low-income zip codes using private wireless networks sourced from their school’s districts, community colleges and universities.

Dallas is planning to follow in San Antonio’s footsteps.

“This is a rare moment in time and no one expected it, but I have been so inspired.” says Dottie Smith, who co-chairs North Texas’ Internet for All coalition and is president of the education nonprofit Commit.

Smith has been working with Barton and 40 different leaders across nine school districts, nonprofits, and city and state governments. The coalition also includes local telecommunication and Internet providers such as AT&T, T-Mobile and Spectrum — who potentially will benefit from private wireless networks because they would receive a large contract with a guaranteed paid bill.

“We are hoping that providers will be able to bring down the cost while keeping broadband speed high enough to allow families to access all of the learning experiences that they need,” Smith says.

Barton explains that this public-private partnership benefits the community.

“You create a win-win for everybody,” Barton says. “The internet service provider gets more business. The school district gets an affordable shared kind-of rate. We public entities get the best rates.”

Who will pay for internet access — and who should?

The Dallas City Council and DISD school board voted in late August to hire CTC Technology and Energy — the same firm used by San Antonio — to create a countywide telecommunications and engineering plan. Hinojosa says the goal is to create long-term county-wide infrastructure to ensure that all students and families have internet access in their homes for good.

The city is contributing roughly $10 million from its CARES Act funds. Hinojosa says the district has budgeted $40 million.

“We have a very healthy reserve,” Hinojosa says. “We could take it out of our savings account. There may be some state dollars.”

He hopes the federal government also will help Dallas and other school districts.

The Federal Communications Commission distributes e-rate money to cities, school districts, hospitals and libraries for broadband infrastructure at government facilities.

At the start of COVID, the FCC chairman temporarily relaxed some of the rules, allowing districts to spend those dollars on hotspots. Hinojosa and other city leaders want the e-rate funds to include families who want to connect to the internet from home, but despite pressure, the chairman has yet to agree to it.

“And then there’s the HEROES Act, which has a lot of infrastructure money in it,” Hinojosa says. Although, he admits that this bill, as well as a couple of others focused on funding internet infrastructure, are stuck in the Senate.

There also is money earmarked in the 2020 bond package, Hinojosa says, should voters approve it on Nov. 3.

“We have multiple financing solutions just in case one of these does not go our way,” Hinojosa says.

“This is extremely important,” he adds. “We don’t know when this pandemic is going to be over. There are some areas that are very underserved with broadband; most of it’s in southern Dallas. Once you connect them, they will have access to telehealth and they can also have access to applying for a job. So, this is a multi-tiered solution for the long-term.”

That’s why Hinojosa is focused on the coalition to help solve a decades-old problem.

“When you have the county, the city, nonprofits, you have these entities involved — then it is a greater solution. It’s just like having water and electricity,” Hinojosa says. “So, that’s why this long-term solution is important, and that’s why we really put a lot of eggs in that basket.”

If all goes as planned, Hinojosa says the district will pilot private virtual networks at five Dallas high schools as early as October — Pinkston, Lincoln, Roosevelt, H. Grady Spruce and South Oak Cliff.

This story was produced through a collaborative partnership between KERA and Dallas Free Press.

Leave a Reply