As schools prep for virtual learning, 1/3 of Dallas families lack internet access

Investigative / Enterprise In-depth examination of a single subject requiring extensive research and resources.

Co-published by our media partner, KERA. Listen to the radio version on KERA’s website.

Jamaala Karim walks into the Paul Dunbar Learning Center cafeteria. It’s filled with staff hired to help distribute technology to students’ families.

“Having to go from single mom to teacher, it’s like, uhhhhhh,” she sighs heavily.

Karim picks up two clear backpacks. Each of them has a Chromebook and headphones for her incoming third- and fourth-graders. She also picks up a hotspot device because her family does not have internet at home.

“It was very difficult,” Karim says, thinking back to the spring semester when the COVID-19 pandemic closed schools. “I think they weren’t really ready for that. When you get on Google classroom, it wasn’t working very well and the WiFi device was acting up a little bit. I kept having to call the school and ask them to fix it, and then I had to go pick up another device.”

Last spring Dunbar distributed 218 hotspots to families of its 515 elementary school students, with even more handed out in August. Principal Alpher Garrett-Jones really wants to make sure her students are prepared for virtual learning this fall. She came to the South Dallas school two years ago to turn the failing campus around.

“What we did was absolutely monumental,” Garrett-Jones explains.

She points to the award on the wall of her office. After Garrett-Jones took over, students’ state test scores earned them a “B” rating, and the school’s grade rose from an F to a C.

So when COVID hit in the spring, Garrett-Jones knew she couldn’t just close her doors like the other schools in Dallas ISD.

“OK so to be honest — we never closed,” Garrett-Jones admits. “We had a porch out on the front. And, so that’s what we did. We gave them the instruction that they needed in order to be successful. We could not afford for it to stop just because of the pandemic.”

Garrett-Jones wouldn’t talk about the barriers most of her students face, but her actions have addressed issues beyond instruction. Over the last two years, she set up a washer and dryer so students could have clean clothes, created a closet for toiletries, and made sure teachers tucked food into students’ backpacks at the end of the day, just in case there wasn’t food at home.

Photo by Keren Carrión/KERA.

Suffice to say, Garrett-Jones anticipated problems with internet access and virtual learning. In a recent Dallas ISD survey, about a third of Dallas families don’t have internet access at home. Garrett-Jones says she couldn’t afford to lose the academic gains she had made at Dunbar because of the digital divide.

And, she’s not alone. School officials and education leaders worry that the current inequities in broadband access will widen gaps in academic performance that existed before the COVID-19 pandemic — disproportionately impacting the poor and students of color.

“I think it’s important to note that it is the district’s commitment to meet that need,” says Jack Kelanic, chief technology officer for Dallas ISD.

Kelanic was hired two years ago to implement Dallas ISD’s long range technology plan. More than $200 million was earmarked for technology in the 2015 bond package so that kindergarten through 12thgrade students would have individual iPads and Chromebooks, and schools would be wired properly to use the devices in the classrooms.

Kelanic says voter support of the 2015 bond put the district in a good position when they were forced to pivot to virtual learning in the spring because of the pandemic.

“I know from communicating with my contemporaries across the state and across the country that not all districts are in this position,” Kelanic says. “It’s very difficult if you’re starting right now to try and find the money to invest in technology to support virtual learning.”

The long range plan for technology outlined in the 2015 bond may have ramped up broadband at school but didn’t do anything for families who lacked internet access at home. So, when the district turned to virtual learning, Dallas’ digital divide became even more apparent.

“It’s definitely a new ballgame,” Kelanic says. “We just find ourselves pivoting a little bit to provide robust internet access for students at home.”

In the last year, the district has spent $2.5 million dollars on hotspots. These small devices, roughly the size of a mobile phone, provide wireless internet access in the home. The City of Dallas and several philanthropic organizations, including the Dallas Education Foundation, also contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to help ensure every Dallas ISD family who needs one can get one.

Kelanic recognizes that hotspots are not the best way to provide internet access. He is aware that they are temporary, expensive and can be unreliable when multiple children are using the same connection.

“I still think that a fixed connection into the home is the best internet solution,” Kelanic says. “I think they tend to be the most reliable and provide the highest bandwidth and you typically don’t have data caps and that sort of thing.”

Kelanic says he is working on long-term solutions with a coalition of school administrators, politicians, nonprofits and internet providers called Internet for All. They are looking at plans to invest in infrastructure in South Dallas and other Dallas neighborhoods so there’s a permanent fix.

“There was just a growing effort to really come together and figure out what a collective impact might look like,” explains Dottie Smith, CEO of Dallas’ education-focused Commit Partnership.

Smith was a teacher in California and a high school principal in Las Vegas before moving with her family to Oak Cliff a few years ago. Soon afterward, she took over as CEO of Commit. The nonprofit has a large local funding base with a few national grants from funders like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

“We still work primarily in Dallas County, but we have a growing advocacy team and a lot of the work that we’ve started to do is statewide.”

When COVID hit, Smith reached out to area superintendents and kept asking, “What are you losing sleep over? What do you need help with?”

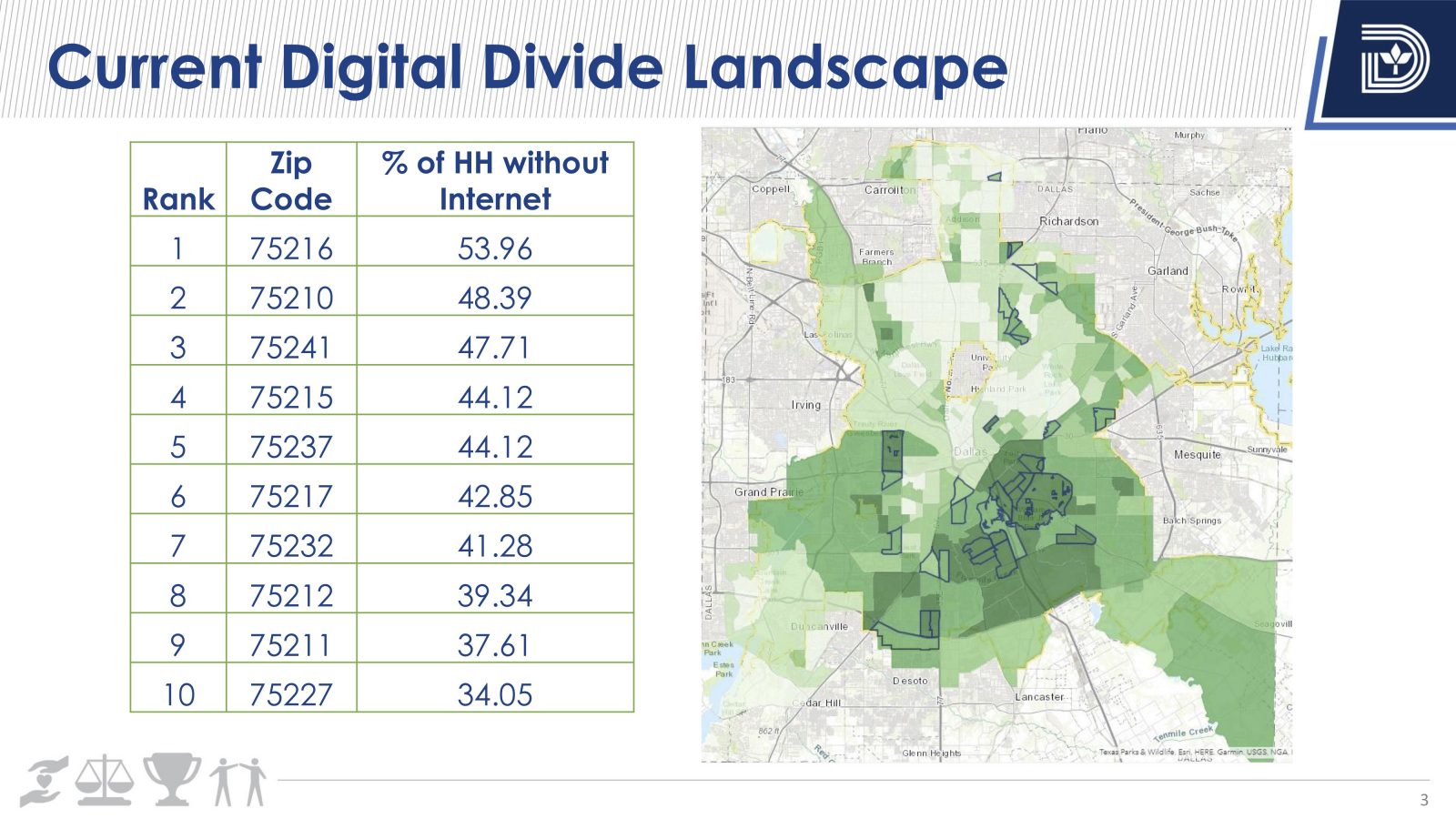

She says internet connectivity was No. 1 on their list. Her team began analyzing U.S. Census data from 2016, which showed that 42 percent of Dallas households lack fixed internet access. This gives Dallas the worst household connection rate among major Texas cities and makes it the sixth worst city in the country.

“We saw that roughly one in 4 households with children in Dallas County are not subscribed to broadband internet, and nearly half of those households are in just 10 zip codes, reflecting the childhood poverty rates that are twice the county average.”

Not surprisingly, she says, these are the same neighborhoods that have crises of economic mobility, high rates of incarceration and poor health outcomes.

“So for a community that’s mired in concentrated poverty, a lack of internet access, especially in this moment of time, stands atop the ever increasing mountain of barriers that significantly hinders a child’s ability to succeed.”

Smith says that data dive led Commit to create Internet for All in May. The coalition is focused on ensuring 100 percent of kindergarten through high school age students have reliable high-speed internet in their homes.

One plan on the table is the possibility of in-home wireless subscriptions with monthly fees totally covered by the school district.

“Now this won’t be for every student, but likely for those in homes with more limited incomes,” Smith says.

Smith says they have been in talks with local telecommunication companies AT&T and Spectrum, and she feels like there will be some really great proposals to consider that will offer a subsidized rate.

“We are hoping that providers will be able to bring down the cost of their monthly subscriptions while keeping the broadband speed high enough to allow families to access all of the different learning,” she says.

The overarching goal is to create a long-term permanent solution for internet access, Smith says, and that means launching a private wireless network paid for with federal funds from the CARES Act. In this model, Dallas ISD and the City of Dallas would place antennas on tall buildings or structures such as light poles and transmit broadband signals to household receivers. This then creates a private wireless network that students can access from their homes.

The coalition is working with an engineering firm to get a better understanding of the cost of the entire project. However, Smith expects the private wireless pilots to be up and running within the year.

“We have to get every kid connected. This is an issue of equity. We have some kids who can easily open the door to the classroom, and for others the door is shut, and that is unacceptable,” Smith says.

Photo by Keren Carrión/KERA.

As the district prepares for the start of school on Sept. 8, Dunbar teacher Brittnay Conner is making her own preparations. She’s spent her own money to buy a webcam, a microphone and editing software to make her lessons more interesting.

“I’m looking to stream from my classroom because I want real-time connection so that they can feel community and building relationships online,” Conner explains.

She also bought special weather-proof boxes that she can leave on her students’ porches. She’ll use the boxes to deliver photocopies of assignments and fresh fruits and vegetables.

“I think broadband is the least of the worries, if I’m being honest right now,” Conner admits. “That’s great if everyone has good solid internet access, but that’s not going to solve all the issues at the end of the day.

“Who is going to sit with them and make sure they can get online?”

School administrators recognize these challenges but are choosing to focus on things they can control to keep the academic gaps from growing in this unprecedented time.

This story was produced through a collaborative partnership between KERA and Dallas Free Press.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Sujata Dand is an award-winning journalist who is energized by change brought in communities in response to news stories. She lives in and has spent most of her reporting career in Dallas, with ample experience covering health care, education and public policy.

“I think it’s important to elevate voices that are often ignored,” Dand says. “For me, that means meeting the people in our communities. We need to see people and listen to them. It’s often a huge act of courage for people to openly share their lives. So, I feel an enormous responsibility in making sure my stories are authentic and fair.”

Dand worked at KERA for almost 10 years, where she produced several television documentaries, including “Life in the Balance: The Health Care Crisis in Texas” and “High School: The Best and the Rest.” She also headed the multimedia project “Boyfriends,” which examined the complex personal and cultural factors that contribute to the way adolescent girls form and maintain relationships. Her work has garnered several local Emmys and national awards including a Gracie for best reality program.

Prior to her work with KERA, Sujata was a reporter and anchor at the CBS affiliate in Wichita Falls, Texas. She has worked as a freelance reporter for NPR and Dallas Morning News. Dand is a graduate of Trinity University in San Antonio.

Areas of Expertise:

health care, education, public policy

Location Expertise:

Dallas, Texas

Official Title:

Senior Editor and Reporter

Email Address:

sujata@dallasfreepress.com