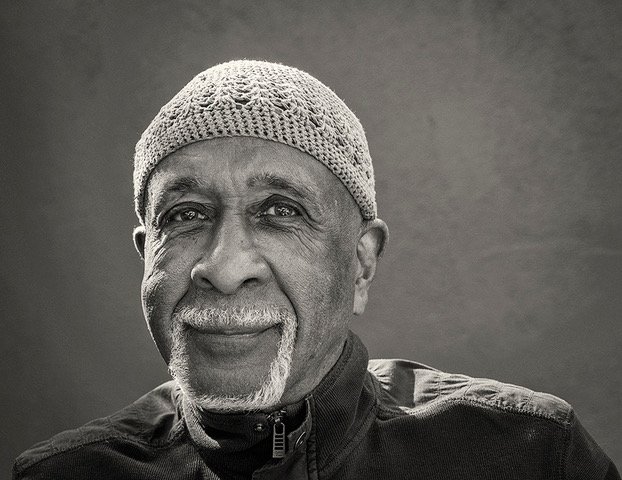

If anyone still believes the notion that Dallas never had a Civil Rights movement, a forthcoming book by one of its sons, Ernest McMillan, will put that myth to rest.

McMillan’s book, “Standing: One Man’s Odyssey through the Turbulent ’60s,” introduces readers to what it was like to grow up in the ’40s and ’50s in Freedman’s Town, which area businesses would advertise as “in the shadows of downtown Dallas,” but for McMillan, “it glistened with light. This was the heart of Black Dallas.”

McMillan left Dallas in 1963 for Morehouse College, and there he found the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, whose national headquarters sat a few blocks from campus. He left school to join the effort, and spent three years working as a field secretary in the Deep South before returning to Dallas in 1967 to establish a SNCC chapter in his hometown.

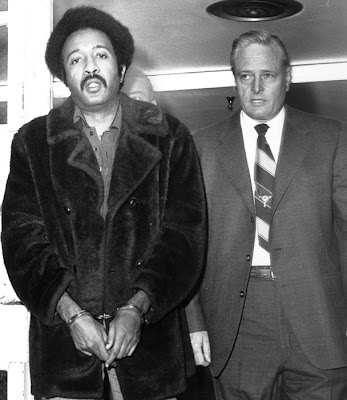

The ensuing chapters tell the story of the struggle in South Dallas where McMillan established the local SNCC offices on Oakland Avenue, now Malcolm X Boulevard. Up the street at Oakland and Pine was the OK Supermarket, part of a “chain of ghetto-gouging stores in South Dallas,” as McMillan describes, where a SNCC-led boycott and protest led to the police slapping felony charges on both him and a comrade for “malicious destruction of private property over the value of $50.”

McMillan explains in the book how he knew he was being targeted by law enforcement officers, who were trying to arrest him and willing to kill him to put an end to the Civil Rights and Black Power movements SNCC was catalyzing in Dallas.

One chapter in the book is devoted to McMillan’s speech to a judge, laying out his case against the unjust justice system from which he was running for his life. Another chapter transcribes the tender letters McMillan wrote from prison to his mother, the late Eva “Mama Mack” McMillan, whose own Civil Rights legacy inspired and fostered her son’s.

McMillan will sign copies of his book, also available for pre-order from local publisher Deep Vellum, at two events this Saturday, Aug. 19: one from noon-4 p.m. during the Tulisoma book fair at the African-American Museum in South Dallas, and one from 4-7 p.m. at Pan-African Connection in South Oak Cliff.

The following excerpt from “Standing,” republished with the McMillan’s permission, is a glimpse into SNCC’s work in South Dallas in the late ’60s.

We activists often relied more on spontaneity and the actions dictated by the moment-to-moment experiences than any theory or formulas. We were in new territories, undergoing a sharp break with our pasts, and treading in piranha-infested waters. One evening, a few of us gathered in a South Dallas lounge, listening to the sounds from a jukebox and testing lessons and arguments gleaned from our community canvasses. In hindsight, this practice was our own version of a classroom, creating verbal and attitudinal responses through a collective rehashing of the day’s events. We were interrupted by someone coming into the bar saying that the cops were outside arresting a youngster for shoplifting at a neighboring convenience store in the same strip mall.

Nothing more needed to be said. We were there in an instant. Some went to “inquire” with the police in loud, irritated voices, while others questioned the store owner. The kid, a seven- or eight-year-old Black boy, was in tears. He stood, sandwiched between two cops who were asking his name, address, and the whereabouts of his parents. Someone recognized the child and described the location of his house so his mother could be notified of unfolding events. The police seemed determined to take the kid to jail or the juvenile home, for stealing and possibly being on the late-night streets, unsupervised.

We were offering a way out for the child to the non-Black store owner, stating we would pay for the cookies or candies the boy supposedly stole. The store owner was unmoved, however, and the police began to handcuff the boy and place him in the squad car. By that time, someone said the boy’s mother was on her way, but the police were in no mood to wait around, especially with the heat we were generating, and justified their stance by saying a crime had been committed and this was “police business.”

One police officer noticed his patrol car had four flat tires. He became alarmed and got on his radio to seek help. A crowd was now building outside the store, and we shifted to teaching mode. We SNCC members seized this as an opportunity to raise consciousness.

“Look at these pigs!” one of us implored the curious crowd. “These cops want to arrest this little boy for some candy!”

“We can pay for the candy!” someone yelled, and others followed suit, shouting, “You’ve got the candy back, honky!” Murmurs and grumblings began to swell within the growing crowd.

“Why do these motherf**kers want to lock him up?” someone asked.

“Don’t they have anything better to do?” another said.

By that time, another patrol car pulled up and the officer in that car joined the other cops. They huddled up, trying to figure a way out. The newly arrived officer got on his radio to call for more help. A wrecker truck arrived, and while its driver attended to the first car’s flat tires, someone pointed out that the second patrol car’s tires were now flat. Two other police cars arrived. The crowd was getting larger and more boisterous.

The lights on the second car were flashing and the cops took on a more defensive stance. One placed the boy in the first patrol car. Finally, a woman arrived claiming to be his mother and demanded to see her son. The police told her that they were charging him with a crime and that she would need to go downtown to get him. Two other cars arrived while we were still in our educating mode among our neighbors.

We began to call out to all that if this store were ours, this never would have happened. “Look at these pigs hassling and oppressing a kid, when the real crooks and criminals roam free to do their crimes,” someone shouted. We reminded onlookers that our people know how to treat each other with respect, but the outsiders who owned our land and controlled our economies were in South Dallas only to take our money and run.

The gathering had bloomed into a full community rally. More squad cars arrived; another police wrecker pulled up. It was even taking on a comical tone as the keystones on site were way out of their league. Given the circumstances, they were required to stay and had no choice but to be the subject of the day’s “lesson” in our makeshift, spur-of-the-moment classroom. Although only ten minutes may have elapsed, it seemed that each second was a blow against the establishment.

Suddenly, someone in the crowd called out, announcing with notes of surprise and glee, that there were now four police cars on flats. We had no idea which member of the crowd was responsible for the flat tires, showing tremendous initiative without any prompting from any of their “teachers.” School was in session and the boy was finally released into his mother’s custody.

Leave a Reply