It’s not uncommon these days for Tracy Lindsey to be driving around in the Bonton neighborhood at 10:30 a.m. on a school day and spot one of the neighborhood children walking down the street.

He’ll pull over and ask, “What are you doing? Aren’t you supposed to be in school?”

The response is usually: “I didn’t feel like logging on today.”

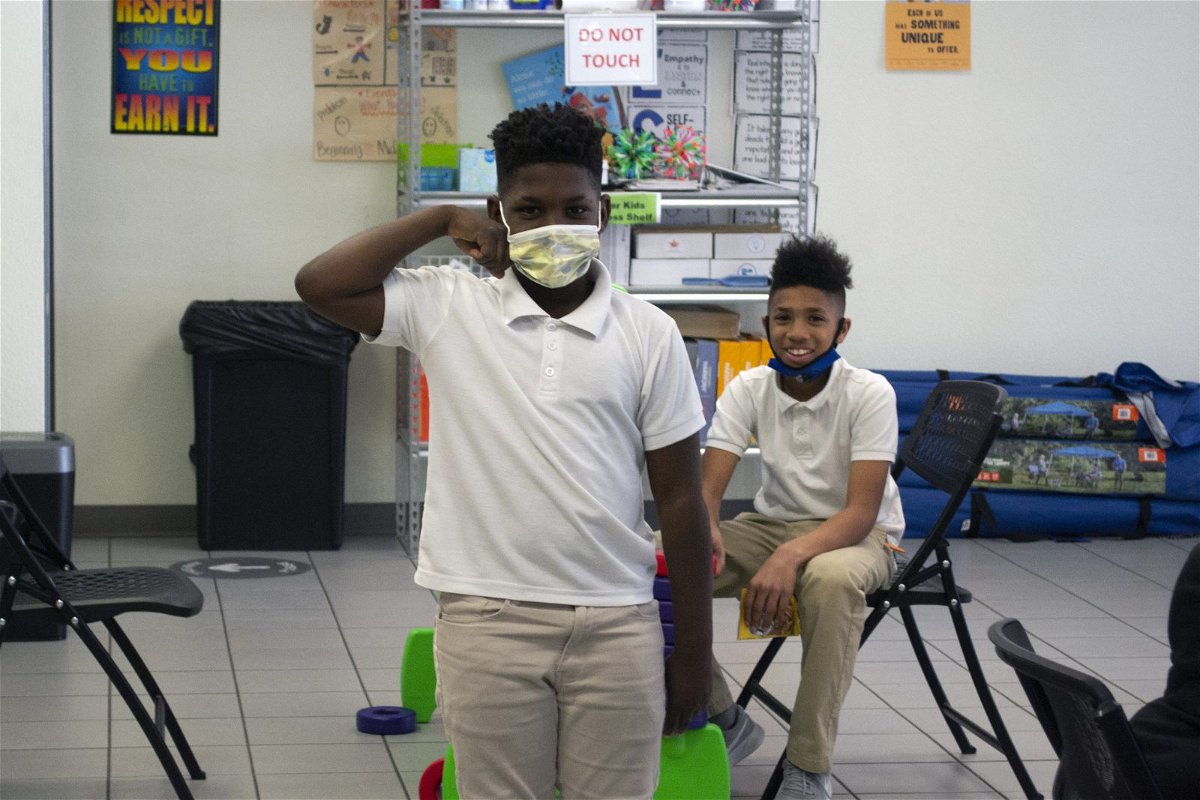

Some children have known nothing but virtual school since last March. Even for those who have returned to campus, the social experience is limited.

“Nothing compares to that face-to-face interaction,” says Lindsey, the kids program director at Bonton’s Bridge Builders nonprofit. He sees the lack of it in his kids’ demeanors and on their report cards.

“Kids that were already behind are even more behind,” Lindsey says, sounding worried.

For many families in South Dallas, COVID has forced them to choose between sending their kids to school and facing financial and health risks, or keeping them home and dealing with isolation and learning loss.

Yasmine Lockett sees similar issues over in South Dallas’ Frazier community. As the Frazier Revitalization education director, she welcomes a few dozen students who come to the center after school, mostly from Paul L. Dunbar Elementary and Billy Earl Dade Middle School.

“Every day, we have to chase them home,” Lockett says. “Home life is too toxic” right now, she says, “because they’re there all the time, and some of them are going crazy.”

All of her middle school students attend classes virtually and walk straight to the center once they log off. Most of her elementary students attend school in person, but they don’t go to recess, they stay in their classrooms for lunch, and they no longer have extra-curricular programs, Lockett says.

Dunbar is still an Accelerating Campus Excellence (ACE) school, she explains, and attendance is one of the crucial datapoints by which the campus is measured.

“They need every child enrolled just to stay afloat with their statistics,” Lockett says. “What can we eliminate to ensure a higher safety level of our kids? Recess, lunchtime interaction, after-school activities.”

It’s part of the reason kids are bouncing off the walls by the time they come to her every afternoon, she says, yet also the reason behavior issues have declined.

“Now it’s, ‘Oh, this is my last resort so let me act accordingly,’ ” Lockett says of her students keeping themselves in check so they have those few hours of social time at Frazier Revitalization.

Though Lockett doesn’t know of any of her students who had COVID this school year, the virus went through several Frazier Revitalization staff members, including her. They had to shut down the after-school program the month of December, and she’s now capped enrollment at 40, even though enrollment usually hovered around 50 or 60 before the pandemic.

“I’m just trying to limit bodies,” Lockett explains.

Bridge Builders opened its after-school program in August but had to shut down last November because of a rash of COVID among staff. They plan to reopen mid-February and are working to turn their computer lab into a library to tackle the literacy problems they’ve seen worsen in recent months.

Even before the pandemic, Lindsey says, “we had fourth graders on a first-grade reading level and eighth-graders on a third-grade reading level.”

He doesn’t fault parents for keeping their children home. When Lindsey came down with COVID, “I was able to seclude myself in the house, had a bathroom attached and a mini fridge. My wife and I had resources that our Bonton parents just don’t have.”

“We have a mother right now that has eight children in a two-bedroom home. If one of those children get COVID, everybody gets COVID — mom, grandma, uncle Leroy …,” he says. “Parents cannot afford to get sick, to lose anything monetarily. Most of the people who work in our community are doing labor that involves human interaction. Everything was shut down for three months, and now that we’re back to work, we have to harness every dollar, cherish every dollar.”

And because of this reality, Lindsey says, “we’re asking a child whose mother may be at work trying to put food on the table to take on the responsibility of an adult to log on to class.”

Even for those kids at school, “there’s fiberglass everywhere and you can’t touch anybody,” he says. “Our kids are just feeling lonely and stressed out. They have lost that human interaction, and there is that fear of not being able to talk to their friends and see their friends.”

This is the reality not just in South Dallas but across the city and the world right now. Despite the academic hurdles for Frazier kids and challenges for working parents, Lockett wonders whether, in some ways, her families might have been more equipped to handle the pandemic.

She wasn’t surprised to see parents in wealthier pockets of the city more willing to send their kids to school in the fall after enduring the stay-at-home orders last spring.

“If you’re accustomed to sending your kids to school and getting back to life, and now all of your kids are home every day,” it’s more of an adjustment, Lockett says.

But “a single mom who’s on welfare with maybe four kids, she’s already always home. And she knows she has to do everything in her capacity to stay afloat to continue with her welfare,” Lockett says.

Virtual school is tough, but the uncertainty of what could happen if you send your child back to school may be tougher, Lockett says. So even if you’re stuck with “one hotspot, and all of you log in at once and the internet is slow, you’d rather stay consistent.”

“I think it really depends on what life you have to give up.”

This story was co-published by our media partner, the Dallas Weekly.

Leave a Reply