The South Dallas Fair Park Public Improvement District is coming to an end. Property owners of neighborhood homes and businesses advocated against extending the PID for another seven years, saying they didn’t feel the additional tax burden translated to tangible community benefits.

“They’ve been collecting, and the only thing you can point to is some Christmas lights on South Boulevard,” says Reverend Al Green of Rugged Cross Church, who owns property in the Fair Park Estates neighborhood.

A Public Improvement District (PID) allows for a group of property owners to request a special property tax assessment for services above what the City of Dallas typically provides. There are 14 PIDs in the city. Residents and business owners pay 15 cents per $100 of appraised value as determined by the Dallas Central Appraisal District, so a home valued at $250,000 would pay $375 a year to the PID.

The South Dallas Fair Park PID consists of about 630 properties and is managed by South Side Quarter Development Corporation, a parent company for developer Matthews Southwest, which owns 10 lots within the PID.

The City of Dallas had proposed a newer and larger PID that would extend to Botham Jean on the west, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Romine Avenue on the south, Dunbar, Robert B. Cullum and Exposition to the east, and Oak and AL Lipscomb Way to the north — almost doubling the PID in size.

South Side Quarter recommended that the additional tax dollars be spent on enhanced security and public safety, capital improvements such as landscaping, lighting, sidewalks, streets, parks, fountains, and roadways, and outreach, business development, and marketing of the PID.

However, neighborhood residents and business owners say despite paying $1.2 million in additional taxes over seven years, they haven’t seen enough positive changes.

The PID budget, provided by the City of Dallas, details how the money has been spent from 2017 to 2023.

With little neighborhood support, South Side Quarter withdrew its petition to renew and extend the PID. They will continue to run the PID until the contract expires in December.

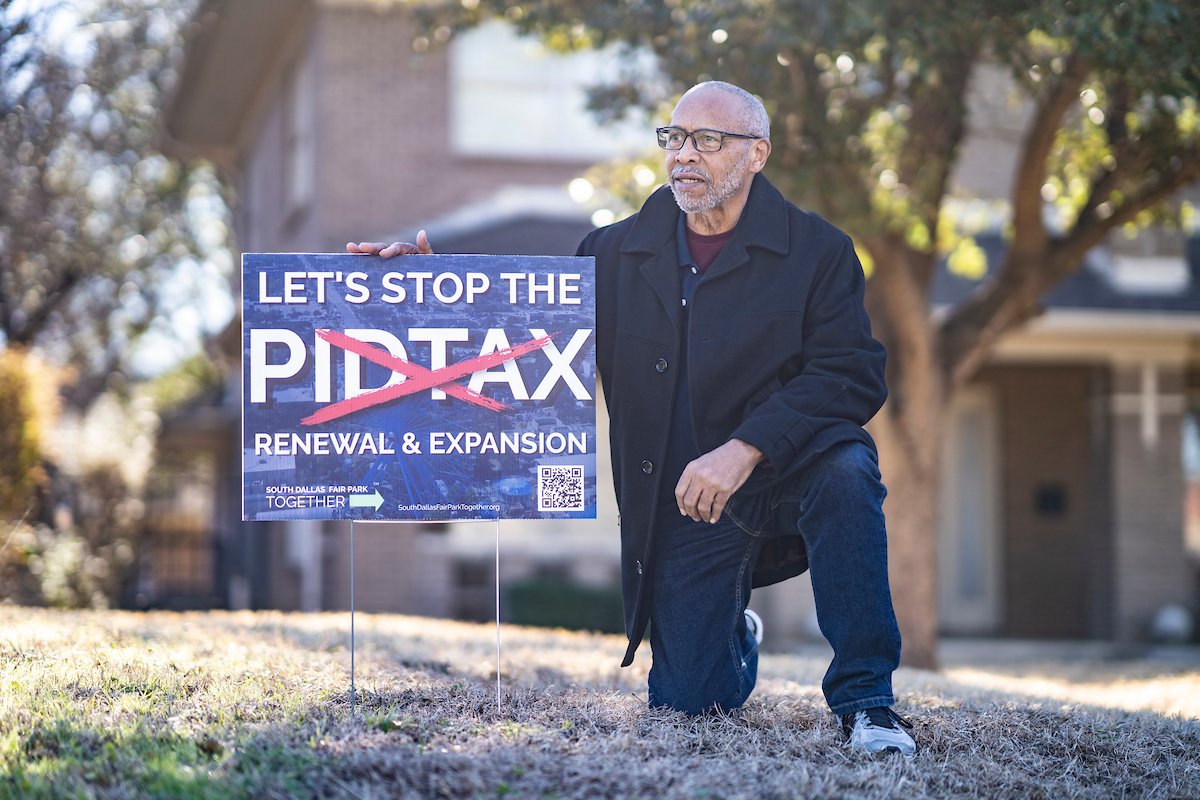

South Dallas property owners campaign to stop the PID.

“What fueled it was [South Side Quarter Development] admitted they hadn’t done that much in our part of the PID,” says Hank Lawson, a neighborhood activist who has lived on Park Row for 20 years. He has had a vital role in the protest against the PID.

Lawson has been making waves in his community since he joined the South Pointe Revitalization Committee April of 2021, five years after the group initially organized. He quickly became a key player and rose to chair the organization.

In the last six months, South Pointe Revitalization has hosted community meetings with South Side Quarter Development and city officials to express their dissatisfaction with handling the PID.

In December 2022, Lawson’s efforts gained momentum when he teamed up with Rev. Green to mobilize their movement with the Dallas Fair Park Together.

Rev. Green says he didn’t realize he’d been paying hundreds of dollars in additional taxes on his properties in South Dallas for the last several years until he received a petition in the mail in December. Green admits that he didn’t see the breakdown of the PID from the rest of his property taxes until he spoke with a friend who lives in the neighborhood.

“As I read the information, it said that by signing this petition, you agree to the assessment, and then that’s when I started connecting the dots,” says Green.

Eager to quit paying the extra tax, he created South Dallas Fair Park Together, a group focused on mobilizing the community to reject the PID.

His team started educating the community about the PID, calling it “taxation without representation,” and support grew. “Stop the PIDTAX” signs began appearing along Park Row Avenue, in front of businesses, and on lots on Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. boulevards.

Green says he believes the PID is a way for the city to collect two property taxes from residents. He urges political leaders to be held accountable for funds that already have been collected.

“They have raised all this money, but no one can track or say where that money went,” said Green.

Green isn’t exactly wrong. Before South Side Development Corporation took over managing the PID in 2018, the PID was managed by Hip Hop Government, Inc. (HHG). The contract was terminated by The Office of Economic Development in 2017 for failure to provide proof of insurance.

The head of Hip Hop Government, Jeremy Scroggins, was involved in a bribery scandal in 2015. He pleaded guilty to using the nonprofit to funnel money between a developer and former city council member Carolyn Davis.

According to a City of Dallas PID coordinator, the funds were not lost, but no records show how the PID funds collected in those first three years were spent. Dallas Free Press has spent the past four weeks pushing to get more information from the city on what exactly happened during the years Hip Hop Government, Inc. managed the PID. City officials have yet to respond.

In December 2018, the South Side Quarter Development Corporation took over the PID with City Council approval.

Shannon Brown-Key manages the PID for South Side Quarter. She understands why the community doesn’t have faith in the PID. She admits that it has been difficult to regain the community’s trust after Hip Hop Government, Inc. failed to administer the PID properly. However, she says the PID money has been used efficiently to help clean up the community by picking up litter and addressing illegal dumping.

“We were able to get many of the goals we set out accomplished,” Brown said. “There were also many cases we were able to aid in the realm of public safety, but for the safety of our security teams, we were not allowed to publicize those. We were able to get several areas cleaned up and maintained.”

Brown-Key says they also tried to build trust with the residents through community-building events such as the MLK and Juneteenth Festivals.

Despite this, Green and others in the community would have preferred to see the PID money spent on security and additional police patrols to make the neighborhood safer. Brown-Key says those kinds of improvements required more money than the current PID provides.

“To make the PID successful, it needed more funding and more resources that are not utilized by tax assessment,” says Brown-Key. “I think equity is going to be a big topic in the future of South Dallas, and for that to work, some historic wrongs are going to have to be made right, that are not on the taxpaying resident’s dime.”

Could the South Dallas-Fair Park PID accelerate gentrification and displacement?

Lawson supported the PID in 2016, but in recent years he was worried that extending and expanding the PID could displace people in the area as property values continued to increase. He says he’s experienced a 64% increase in the appraised value of his property in just the past two years.

According to D Magazine’s neighborhood data from 2016, when the PID was first established, about 37% of South Dallas-Fair Park owned their homes, most rented. And about a third of the residents live below the poverty level, with a typical household income of roughly $24,000.

Lawson argues that the PID tax was just another way to force property and homeowners out in the long run, emphasizing that the expanded PID, if approved, would have been in place for the next seven years.

“There’s a potential for displacement; our neighborhood has seen record increases in appraised value,” Lawson says. “There is a record increase in property value, and then you add on the expansion of the PID and some of those residential areas. All that’s going to be passed on to the community, and they’re going to be forced out behind the PID increases, so we’re seeing that that is a vehicle for displacement.”

Brown-Key says South Side Quarter became aware of the community’s concerns last August and met with Lawson and his group, Pointe South Revitalization, to “garner support and explain renewal” during the August, September, and November meetings.

However, Brown-Key didn’t change Lawson’s mind. He and other residents met with Dallas City Councilmember Adam Bazaldua in January to discuss their worries of displacement.

Bazaldua released a statement soon after saying he would not support the PID and would spend all of 2023 working with the community to develop a better plan. PID promised to beautify South Dallas and make it safer. Neighbors say that promise was broken. Shanay Wise and her children have lived on Park Row in South Dallas for five years, the first home Wise has ever owned. She also plans to launch a brick-and-mortar business for her catering company in the PID.

But Wise says she has yet to receive an invoice of how much she contributes to the PID. The information on Dallas Central Appraisal District’s website for her property shows that she’s in the PID but doesn’t show how much she paid in her 2022 tax bill.

Wise says she and other neighbors just want a say in how the money is spent.

“We don’t understand why we’re not a part of that process,” she says.

Brown-Key says the South Side Quarter held annual meetings, but they were poorly attended.

Wise says one meeting a year isn’t enough.

“In other cities, they’re sitting at the table with the people that are controlling the money of the PID. They’re saying, ‘Hey, we need this. Hey, this is going wrong — can you put this money here?’ They’re able to do that, but we don’t get that opportunity,” she says.

Despite her frustrations, Wise remains optimistic about the potential benefits of a well-implemented PID. She believes the PID could have been good for South Dallas. Wise says a longtime friend who lives in the Oak Lawn area has been telling her about the Oak Lawn PID and how meetings and other necessary actions were being taken.

Wise was disappointed that her neighborhood’s PID couldn’t accomplish what it was meant to do.

“That just broke my heart,” she says.

I had hoped for the past 50 years that someday former Dallas City Council woman Elsie Fay Higgins’ hard defiant work in South Dallas would have not been in fain. She tried her very best to let South Dallas remain South Dallas. She held onto the premise until she had to be “taken away” to some unspecified place because of these circumstances. She put up “The Good Fight” to save the homes and businesses of Fair Park. We kept wondering when would THEY be back to make a claim. But I can’t believe they are asking this low-income community to “foot the bill” twice! When will it end? Of course, I say, “Defund the Police”. (Our Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson and I agree to disagree on that point and remain very good corresponding friends.) Take care, All. Thanks for sending me the article”

Gwen McAfee

*****Please, change my email to GXMDHASERVICES@PROTON.ME